- Home

- Claudia Mills

Alex Ryan, Stop That! Page 9

Alex Ryan, Stop That! Read online

Page 9

“I’m glad I was there when it happened,” he said. It occurred to him that so far no one had questioned why he was there when it happened. Perhaps it was better not to call attention to the odd coincidence.

Marcia didn’t miss her cue this time. “I’m glad you were there, too,” she said softly. “Thanks, Alex.”

He flashed her his friendliest grin. “Anytime,” he said.

“Marcia, our ride is here,” Mrs. Martin called. Mrs. Martin was going with Marcia to the emergency room, to stay with her until her parents arrived.

The ranch guide and another dad appeared to carry Marcia to the truck.

“Good luck,” Alex called after her, the friendly grin fading from his face. In his last glimpse of her, Marcia looked small and scared, her face white again with pain as her ankle was inevitably jostled. The truth was that Marcia would have a cast on her ankle for weeks, she would miss swimming and tennis, and it was all Alex’s fault.

Alex lay back weakly on the couch. He was so hungry he almost felt sick to his stomach. Or was it the guilt about his unconfessed role in the accident that was making his stomach churn?

It wasn’t as if he had done anything that terrible, Alex reasoned. The terrible consequences were as much Marcia’s fault as his own. Just because you thought you heard a rattlesnake didn’t mean you had to run down the trail like an idiot and not look where you were going and trip and break your ankle. All the same, even though he hadn’t planned for any of this to happen, none of it would have happened if it hadn’t been for his plan.

The ranch guide returned. He plunked himself down on the arm of Alex’s couch. Alex hoped he wasn’t going to make another speech about what a big hero Alex had been.

“Poor little thing,” the guide said, obviously referring to Marcia.

Alex remembered that the guide’s name was Sam. Sam sighed, as if doubtful that Marcia would live through the truck ride to the hospital. Alex could imagine that it wouldn’t be all that comfortable riding in the back of a truck for twenty miles on bumpy, rutted dirt roads.

“We’ve had broken bones before,” Sam said. “And a concussion—no, make that two concussions. Hypothermia—I’m surprised you folks didn’t get it today, out there in the rain, with insufficient rain gear. Insect bites. Poison ivy. Yup. We’ve seen it all, just about.”

The memory of past calamities seemed to cheer Sam. Maybe he enjoyed playing the role of hero, too.

“Not snakebite, though. We’ve never had a case of snakebite. Not in the six years I’ve been working here. We go ahead and warn folks about snakes—standard procedure, warn ’em about everything. But I think this is our first report of a snake encounter, especially at this altitude and on an overcast day. Those critters usually lay low and don’t rattle unless someone disturbs them sunbathing on a rock.”

Alex squirmed. His stomach squirmed with him.

“Let me ask you something, son. You think these girls really heard a snake? Seems unlikely to me. You know how kids are. Girls especially.” He winked at Alex; Alex didn’t wink back. “You think it was all in their minds, like? Something they talked themselves into thinking they heard?”

“I don’t know,” Alex said uncomfortably. “Maybe.” But he didn’t want Sam thinking Marcia and Lizzie were hysterical, either. “Lizzie is pretty reliable.” That made it sound as if Marcia wasn’t. But Sam wasn’t going to see any of them again, after tomorrow, so it didn’t much matter what he thought.

Alex’s father appeared and perched on the other arm of the couch. He looked down at Alex, his face beaming with fatherly satisfaction, even though his smile was still slightly mocking.

“Feeling better?”

It was too much, to be trapped between his father on one arm of the sofa and Sam on the other.

“Actually,” Alex said, “my stomach doesn’t feel so hot.” His stomach was back on the bus again, lurching over the twisting switchbacks of the mountain pass.

He was going to be sick. He got up unsteadily from the couch and staggered toward the door and threw up in the dirty snow bank beside the porch.

Before stumbling inside again, he remembered to hurl his snake rattle as far as he could into the twilight.

13

THE NEXT MORNING, THE THIRD-PERIOD family-living class made pancakes; the second-period family-living class made scrambled eggs and sausage cakes; the fourth-period family-living class prepared a fruit platter. It all looked surprisingly good, but Alex’s stomach still wasn’t ready for it. He ate half a pancake, then pushed his plate away.

Dazzling blue skies greeted them when they stepped out of the cabins for the hike back.

“Don’t forget sunscreen,” Ms. S. reminded the clump of kids standing near Alex.

Alex found his bottle of sunscreen in his pack. Unfortunately, he hadn’t put the cap back on tightly enough the last time he used it, and the bottle was sticky with spilled sunscreen. So was the balled-up, still clammy T-shirt that he had stuck in there yesterday after the storm and forgotten to take out again. The whole thing was pretty disgusting. Alex smeared some sunscreen on, stuck the bottle back in his pack, and zipped it shut again.

As the seventh grade started hiking, Dave fell into step beside Alex. Alex was relieved to have Dave as his partner again: with Dave he didn’t have to keep on pretending to be a hero. But he hoped Dave wasn’t going to be asking him for any more plans. Alex was finished with plans for the rest of his life.

“Man, my legs are sore,” Dave began. “And my shoulders. And my arms.”

“Yeah,” Alex said. “Mine, too.”

They walked for a while in silence. That was the best thing about being a guy, Alex thought: you could walk along with somebody and not have to be yakking all the time. Up ahead, he saw Lizzie yakking with Alison. Was she still yakking about him? He hoped not.

In his head Alex heard Sam-the-ranch-guide’s voice: “All I can say is that it was a lucky thing for this young lady that you happened to be so close at hand when the accident happened.” He saw his dad, hovering protectively by him, that proud look in his eyes, asking, “Feeling better?”

He wasn’t feeling better. If anything, he was feeling even worse.

“It wasn’t really our fault,” Dave said, out of the blue.

Alex just looked at him. The denial, which had seemed plausible enough yesterday when Alex had made it to himself, sounded thoroughly pathetic when said aloud.

“Well, not a hundred percent our fault,” Dave amended.

“Ninety-eight?” Alex asked.

“No more than ninety.” Dave flashed him a grin. Then he turned serious again. “You’re not going to say anything.” The statement was clearly a question.

“No.” What would be the point? What was done was done. A big dramatic confession wouldn’t miraculously heal Marcia’s broken bone. And if he spoke up now, everyone would wonder why he hadn’t said anything before, when Lizzie was telling her story, when Sam was leading the others in applause. If he spoke up now, he’d just make himself—and everybody else—look ridiculous.

Because the hike back to the lodge was mostly downhill, unlike the hike up to the cabins, they made much better time and reached the lodge picnic area by mid-afternoon.

“Free time until dinner,” Coach Krubek announced. “We’ll eat at five-thirty.”

“Nature journals!” Ms. S. sang out. “We’ll be sharing from our journals in our program tonight.”

Alex wasn’t going to be sharing anything from his nature journal, that was for sure. Its pages were completely blank, except for his rain poem, which he didn’t feel like reading to anyone now.

Then he remembered: hadn’t Ms. S. said that their nature journals were worth 10 percent of their English grade for the trimester? Wearily, Alex fished his journal from his backpack. It, too, was covered with spilled sunscreen.

“You’re kidding,” Dave said when he saw what Alex was doing.

“It’s part of our grade,” Alex said. “I have to write somet

hing.”

“I’m getting a C in English already,” Dave said. “See ya later.”

Alex sat himself at a picnic table, wiped sunscreen off his pencil, and started writing. He remembered a lot of things he had seen on the hike. Juniper bushes. Pine trees. Tiny darting chipmunks. One lone circling hawk. He was pretty good at drawing, so he made a picture of the hawk on one page.

When he glanced up from his drawing, he saw Ms. S. standing a few feet away, watching him. “Write about your experiences yesterday,” she suggested in her low, gentle voice. “It was a wonderful story when Lizzie told it last night. I’d love to hear your version in your journal. You could read it to all of us this evening during our sharing time.”

Alex gave a noncommittal smile; Ms. S. walked away. He could just imagine the journal entry he would write about his heroic rescue of Marcia:

So Marcia had been giving me the cold shoulder, see? So I decided to play a trick on her. I had this rattlesnake rattle that I had brought to camp just to cause trouble for somebody, and so I hid behind some bushes and rattled it, and made this rustling sound. And the rest is history.

Yeah. Right. He was going to share that with the group tonight?

Alex wrote a paragraph describing the lightning storm and then closed his journal and put it back in his pack, which now reeked of sunscreen. If Lizzie read aloud from her journal, that should take up the whole sharing time, sparing everybody else.

Sometimes, Alex was learning, silence was best.

Alex tuned out during most of the evening program. There were lots of descriptions of trees and birds and clouds and rain. Lizzie’s were definitely the most poetic. Ms. S. looked at him inquiringly the first time she called for volunteers. He gave a slight shake of his head, and after that she left him alone.

Friday morning they went on a shorter hike to see some Indian ruins. The ruins looked like a bunch of broken bricks to Alex. Mesa Verde this wasn’t. Mrs. Martin, back from the hospital, led the tour. But first she answered some questions about Marcia.

“Her right ankle is broken,” Mrs. Martin said. “The doctor said it was a clean break, broken in just one place, and should heal well. They put on a cast and gave her a pair of crutches, which she’ll need for about six weeks.”

That didn’t sound too bad. Six weeks wasn’t that long. It would leave Marcia the second half of the summer for her swimming and tennis. And everybody would make a big fuss over her at school, when she hobbled in on her crutches. Alex knew Marcia would see to that.

After the hike, they returned to the picnic area and ate the box lunches provided by the ranch. As soon as Alex sat down at his table, other kids flocked to join him. Dave, of course, and Ethan and Julius. Even some of the girls. Marcia’s friend Sarah made a point of stopping by to tell him how wonderful he was: “I just want to say that I think it’s, like, great, what you did for Marcia.” Tall Tanya, Alex noted with alarm, had taken to gazing at him with adoring eyes.

Alex had a feeling that if there were another square dance right now, he wouldn’t be partners with Mrs. Martin. The girls would be lining up to dance with him. Even Marcia.

Except that, in the hospital with a broken ankle, Marcia couldn’t dance.

The bus ride home was as bumpy and curvy as the bus ride to the ranch, but Alex managed to sleep most of the way. When he staggered off the bus back in West Creek, queasy and stiff-legged, his mother was there to greet them. She gave Alex a long, tight hug and then turned to kiss his dad.

“The house was so quiet without you two!” she exclaimed. “Cara and I were going crazy, listening to ourselves rattle around in it.”

“Where was Dax?” Alex’s dad asked. “Was he rattling, too?”

Rattling. Alex cringed. His mom ignored the question, instead giving Alex another hug. Something about the hug—the sense that his mother had really, truly missed him, that she really, truly loved him no matter what—made Alex fight with himself to hold back tears.

“So,” she said when she finally released him, “how was it? Tell me all about it. I want to hear everything.”

“Good!” his dad said. “Because we have some stories to tell.”

Always one to seek maximum dramatic effect, his dad didn’t launch into the big story in the car. He told about the mountain biking: “I may be pushing fifty, but let me tell you, none of those kids were passing me on the trails.” He told about the ranch’s great barbecue the first night: “I hate to say it, hon, but you have some competition in the cooking department.”

Alex was relieved that he didn’t tell about the square dancing: And when the girls had finished picking their partners, guess who was left over? Yup, you guessed it. Our son, Alex.

When they reached home, Cara’s car was parked in front of the house. “Is Lover Boy here, too?” Alex’s dad asked, not seeming to expect an answer.

Both Cara and Dax were in the kitchen, eating a snack. Cara, not usually one for hugging, got up to give Alex a quick squeeze. Dax raised his hand in greeting. He was wearing the diamond stud. Alex saw his dad’s eyes go to it, too.

“You survived,” Cara said.

“Barely,” his dad said, settling himself into a kitchen chair. He was obviously ready to tell the story now. Alex had the sense that he didn’t even mind Dax’s being there. The bigger the audience, the better.

“Uh-oh,” his mother said. “Is this something I want to hear?”

“You bet it is.”

Alex’s dad told the story, pretty much the way Lizzie had told it. He threw in an impersonation of Marcia, squealing as she ran away from the “snake.” He made a bit more of Lizzie’s thinking Marcia might be dead. He gave more fanfare to Alex’s heroic arrival upon the scene.

His dad was a great storyteller. None of the others seemed to think it odd that his dad was telling Alex’s story, not Alex. They were used to listening to his dad talk. Alex wouldn’t have wanted to tell the story, anyway. It was a big enough lie just to listen to it. It would have been a monstrous lie to tell his dad’s version of it himself, in his own words.

He felt his mother’s eyes on him, filled with pride. That was how she always looked at both her children. Cara seemed impressed in spite of herself, as if she hadn’t suspected that her kid brother had it in him. Dax gave Alex an approving smile, but there was a question in his eyes. There was no way he could have known the truth. Maybe he was puzzled by Alex’s unsmiling silence during the telling of his triumph.

“You two must be starving,” Alex’s mother said when the story was finished. “I hope so; I made a cake.”

Alex ate a thick wedge of it while his dad went upstairs to check his e-mail and his mom went downstairs to check the laundry.

“You’re not into it, the whole hero thing,” Dax observed.

Alex would have been “into” it, if he had really been a hero. “Well, it’s just—I mean—I really wasn’t a hero. It really didn’t happen—completely—the way Dad said.”

Maybe he had already revealed too much.

Cara laughed. “When has anything ever happened completely the way Dad said?”

“It’s not just Dad. It’s everybody. Saying this. Saying that. I guess I’m just tired of hearing it, that’s all. It’s like—just because they think something is one way doesn’t mean it is that way.”

“Remember Thoreau?” Dax asked.

“Sort of.”

“‘What a man thinks of himself, that it is which determines, or rather, indicates, his fate.’”

Alex carried his empty plate to the dishwasher. That was the whole problem, right there. His dad, his mom, his sister, his teachers, Sam-the-ranch-guide, Marcia, his friends—with the exception of Dave, they all thought he was a hero. In the opinion of the rest of the world, he was doing great. He was the only person who had a low opinion of himself right now. But if Dax and Thoreau were right, his was the only opinion that counted.

His father looked up from the computer, seeming surprised at the sight of Alex, positioned in t

he door to the home office. “Two hundred and fourteen e-mails,” Alex’s dad said. “And I even checked my e-mail from my laptop at the ranch this morning.”

“Dad.” Alex didn’t know if he could get the words out. “Do you remember the real rattlesnake rattle Grandpa gave me that time?”

“Sure. What of it?”

“Well, the rattle Marcia and Lizzie heard on the trail—”

Alex didn’t have to finish his sentence. His dad gave a hearty guffaw. “I should have figured it out. That guide Sam kept saying that they’d never had an encounter with snakes on the trail before. My son, the hero! Oh, this is a good one!”

His dad didn’t look angry. Alex knew this was the kind of prank his dad could have pulled when he was young.

“I have to say something. I mean, to somebody.”

Alex’s dad’s face changed.

“I mean, I can’t take it anymore, everybody going on and on about it when it was all my fault in the first place.”

“You’re joking, aren’t you?” His dad’s voice was harsh and critical now. “Are you crazy? If you thought yakking about that broken tree branch would cause trouble, what about some kid’s broken bone? You want her dad suing me for all their hospital bills? Use your head, Alex. Right now you have it both ways. You had your fun, and you got to be hailed as a hero afterward. It sounds pretty good to me.”

“But it’s all a lie,” Alex said desperately.

“Look. Half of what I do as a lawyer is to lie. No, not to lie, exactly, but to be selective about what truths I tell, and when and where, and to whom. Let this die down of its own accord. You blow the lid open on this thing, Alex, and you’ll be the laughingstock of your school, and your mother and I will be the laughingstock of the PTO. There is a time for talking, the Good Book says, and a time for keeping your mouth shut. This is a time for keeping your mouth shut.”

There was so much else that Alex wanted to say, that he needed to say. Not now, and not to his dad. But someday, to somebody. He didn’t know how he’d tell the truth—could he really walk up to Marcia and just say it?—but he knew he’d tell it somehow. He didn’t have to act the way his dad acted. He didn’t have to do the things his dad would do. In the end it didn’t matter what his dad thought of him, or said about him, to his friends, to his coach, even to the whole school. What mattered was what Alex thought of himself.

Standing Up to Mr. O.

Standing Up to Mr. O. Lucy Lopez

Lucy Lopez Dinah Forever

Dinah Forever Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star

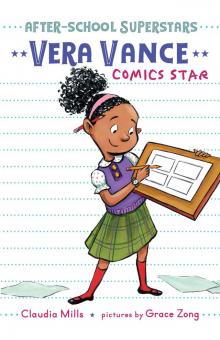

Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star Vera Vance: Comics Star

Vera Vance: Comics Star Izzy Barr, Running Star

Izzy Barr, Running Star You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman

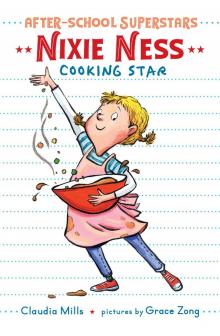

You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman Nixie Ness

Nixie Ness The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish

The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish Basketball Disasters

Basketball Disasters Being Teddy Roosevelt

Being Teddy Roosevelt Losers, Inc.

Losers, Inc. The Trouble with Friends

The Trouble with Friends Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ

Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants

The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants Annika Riz, Math Whiz

Annika Riz, Math Whiz Fourth-Grade Disasters

Fourth-Grade Disasters Pet Disasters

Pet Disasters The Trouble with Ants

The Trouble with Ants Write This Down

Write This Down Alex Ryan, Stop That!

Alex Ryan, Stop That! Kelsey Green, Reading Queen

Kelsey Green, Reading Queen How Oliver Olson Changed the World

How Oliver Olson Changed the World Lizzie At Last

Lizzie At Last Zero Tolerance

Zero Tolerance The Nora Notebooks, Book 2

The Nora Notebooks, Book 2 Cody Harmon, King of Pets

Cody Harmon, King of Pets Fractions = Trouble!

Fractions = Trouble! Makeovers by Marcia

Makeovers by Marcia One Square Inch

One Square Inch