- Home

- Claudia Mills

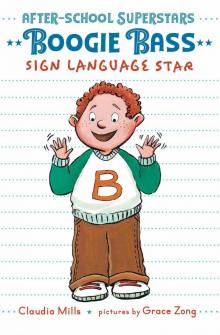

Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star

Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star Read online

OTHER BOOKS IN THE AFTER-SCHOOL SUPERSTARS SERIES

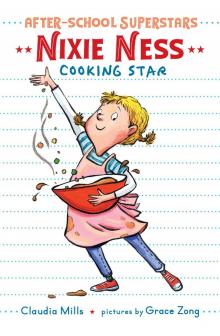

NIXIE NESS

COOKING STAR

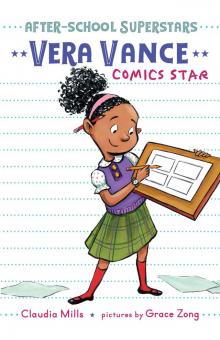

VERA VANCE

COMICS STAR

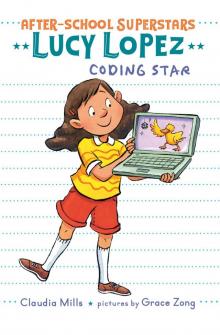

LUCY LOPEZ

CODING STAR

The publisher wishes to thank Mary Darragh MacLean of Sign Language Resources, Inc. for her expert help.

Margaret Ferguson Books

Text copyright © 2021 by Claudia Mills

Pictures copyright © 2021 by Grace Zong

All Rights Reserved

HOLIDAY HOUSE is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

www.holidayhouse.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mills, Claudia, author. | Zong, Grace, illustrator.

Title: Boogie Bass, sign language star / Claudia Mills; pictures by Grace Zong. | Description: First edition. | New York City: Margaret Ferguson Books, | Holiday House, [2021]

Series: After-School Superstars; #4 | Audience: Ages 7–10.

Audience: Grades 2–3. | Summary: Boogie Bass feels his best friend, Nolan, is better than he is at everything, even caring for Boogie’s little brothers, but an after-school camp reveals Boogie’s talent at communicating using American Sign Language. Includes facts about ASL.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020013531 | ISBN 9780823446292 (hardcover)

ISBN 9780823449361 (trade paperback)

Subjects: CYAC: American Sign Language—Fiction. | Family life—Fiction.

Self-confidence—Fiction. | After-school programs—Fiction.

Schools—Fiction. | Classification: LCC PZ7.M63963 Bq 2021 | DDC [Fic]—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020013531

Hardcover ISBN 9780823446292

Paperback ISBN 9780823449361

Ebook ISBN 9780823450466

a_prh_5.7.0_c0_r0

Contents

Cover

Other Books in the After-School Superstars Series

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Some Facts about Sign Language

Acknowledgments

About The Authors

To Kate Simpson, my raft buddy

Boogie Bass lifted his eyebrows, bugged out his eyes, and stretched his mouth into a grin so big it made his cheeks hurt. Maybe now his littlest brother would stop crying.

Bing didn’t.

Boogie wiggled his nose. He waggled his fingers in his ears.

Bing cried even harder.

It was all Boogie’s fault. He was the one who had left Bing’s bedroom door open. The family dog, called Bear because he was as big as a bear, chewed anything left lying on the floor.

Shoes.

Crayons.

Homework.

The remote for the TV.

And now, Bing’s little stuffed dog that he carried everywhere. Doggie-Dog no longer had a head, just a small soggy body. Boogie had banished Bear to the kitchen for this terrible crime.

As Bing clutched what was left of Doggie-Dog, Boogie picked him up and held him on his lap. He wrapped his arms around Bing’s shaking shoulders.

“What do we do now?” he asked his best friend, Nolan, who had come over to spend a snowy Sunday afternoon hanging out together.

But even Nolan, the smartest kid in the entire third grade at Longwood Elementary, had nothing to offer but a sad shrug.

Boogie’s dad was at work. He was a plumber. “Toilets don’t just overflow on weekdays,” was one of his dad’s sayings. His mom was in bed with a migraine headache. Boogie knew better than to bother her unless someone was dripping blood on the carpet.

As Bing continued to sob on Boogie’s lap, his other two brothers raced into the living room, the bigger one chasing the smaller one and both screaming at the top of their lungs.

“I’m going to get you!” T.J. shouted.

“Nooooo!” shrieked Gib, his shirt left behind somewhere—probably being chewed right this minute by Bear.

All four brothers had fancy names. Their mother, who was generally a very unfancy person, liked names that sounded elegant. But they had all ended up with unfancy nicknames. Nine-year-old Boogie’s real name was Brewster. Six-year-old T.J.’s real name was Truman James. Four-year-old Gib’s real name was Gibson. And two-year-old Bing’s real name was Bingley.

“What’s wrong with him this time?” T.J. asked, giving up the chase to point at Bing.

“Bear ate Doggie-Dog’s head,” Boogie explained.

T.J. burst out laughing. Gib, who copied everything T.J. did, laughed even harder.

“It’s not funny!” Boogie told them. Except it would have been, if poor Bing wasn’t crying so hard.

Boogie had to think of something to make Bing stop crying. He looked at the flakes swirling outside the window and the thick layer of snow already frosting the yard.

“Let’s go sledding!”

Nolan shook his head. Boogie suddenly remembered the work it would be to dig up four snow jackets, four pairs of snow pants, four pairs of snow boots, four pairs of snow mittens, and four snow hats, plus stuff for Nolan, too.

“Let’s go indoor sledding!” Boogie said. “The stairs can be the Olympic sledding course. No, the Olympic luge course. We can use the laundry basket for the luge.”

Nolan shook his head again, but T.J. had already dashed into the laundry room and returned with a large plastic tub.

“There was some stuff in it, but I didn’t know if it was clean or dirty, so I dumped it out on the floor,” T.J. said. “Don’t worry, I closed the laundry room door so Bear can’t get in there to chew it. Or at least I think I did.”

The next thing Boogie knew, T.J. and Gib were sitting in the laundry basket at the top of the stairs.

“Give us a push!” T.J. called to Boogie and Nolan.

“I don’t think your mom is going to like this,” Nolan said to Boogie. But Boogie couldn’t disappoint the others now. He set Bing down on the couch, climbed up the stairs, and gave the laundry basket a hard shove.

Down the stairs it clattered, riders screaming, Bear howling from the kitchen, where he knew he was missing out on all the fun.

“Gold medal!” T.J. shouted as they crashed into the back of the couch.

“Again!” Gib shouted. “Go fast again!”

After the second crash-landing, T.J. pumped his fist into the air. “Is there something even better than a gold medal? Like a chocolate-covered gold medal?”

“Again!” Gib continued to shout.

At least Bing had stopped crying. But Boogie saw Bing looking toward the laundry basket with longing in his eyes. Quiet little Bing hardly ever got a turn at anything.

“It’s Bing’s turn,” Boogie announced.

“Awww!!” T.J. and Gib complained.

“It’s Bing’s turn,” Boogie repeated.

Boogie carried the laundry basket back up the stairs and helped Bing, who was still clutching Doggie-Dog, climb into it.

“Ready?” he asked.

Bing pointed at Boogie, then at the basket. Bing hadn’t started talking very much yet.

“You want me to get in with you?” Bo

ogie asked. “Okay, here we go!”

Just as he shoved off, from the corner of his eye, Boogie saw Nolan frantically drawing a line across his neck with his finger, clearly the sign for Disaster heading your way RIGHT NOW!

Behind Nolan stood Boogie’s mother.

But it was too late to stop anything.

Down went the basket, sailing past the couch this time into a narrow table, where his mother’s favorite vase stood full of flowers.

Crash!

Where a vase used to stand, and used to be full of flowers.

Water splattered. Shattered pieces of glass flew everywhere. One of them hit Bing in the cheek, and he began crying again.

“Brewster Bartholomew Bass!” thundered his mother. “What on earth are you doing?”

“Um—indoor luge?”

“And whose idea was this?”

“Um—mine?”

“Oh, Boogie.” Now his mother looked close to tears, too. “And they say the oldest child is supposed to be the responsible one. Boogie, all I wanted was one hour of peace and quiet. Not one hour of indoor luge!” She turned to Nolan. “Tell me, do you organize indoor Olympic winter sports at your house? Never mind, I know the answer to that one.”

Nolan had already retrieved a towel, broom, and dustpan from the kitchen and was sopping up the spilled water and sweeping up the vase pieces. He spent so much time at Boogie’s house he could find whatever was needed even better than the people who lived there.

Just then Boogie’s mother’s eyes fell upon the headless body of a certain stuffed dog that had fallen out of the laundry-basket-luge when it crashed.

“Oh, no,” she said. “What happened here?”

“I left Bing’s bedroom door open,” Boogie muttered.

“Oh, Boogie! Nolan, in your house, do people forget to follow very simple instructions about very simple things like closing doors? Never mind, I know the answer to that one, too.”

Boogie’s mother was right.

Nolan would never think up anything as dumb as indoor luge. And Nolan would never have forgotten to keep Doggie-Dog safe from Bear.

If Nolan had been the oldest brother in Boogie’s family, Bing wouldn’t be in tears right now.

Boogie had always been proud to have a friend as smart as Nolan. In the after-school program they attended together, Nolan had been the best at chopping and measuring in cooking camp. In comic-book camp, Nolan had known tons of cool facts about the history of comics. In coding camp, Nolan had been the coding wizard. Boogie hadn’t been very good at cooking, or drawing, or coding. Actually, he had been pretty terrible at all of them, but the camps had always been tons of fun.

Now they were starting a four-week sign-language camp on Monday. Boogie would bet a hundred chocolate-covered gold medals that Nolan would be really good at sign language, and a hundred times better at it than he was.

Nolan was better at everything than Boogie was, even better at being a brother.

“Boogie, do you ever hear anything I say?” his mother asked.

It was clear his mother didn’t expect him to give a reply.

So Boogie helped Nolan with the sweeping as his mother carried Bing off to get a Band-Aid, leaving Doggie-Dog’s headless body behind on the floor.

Maybe in sign-language camp they’d start out by learning the sign for I’m sorry. Right now, that would be a very useful thing for Boogie to know.

Right now, he was sorry about everything.

The third-grade sign-language camp was held in Boogie’s old second-grade classroom. He gave a fond smile to the pictures of “community helpers” displayed on the bulletin board.

Once Colleen, the head camp lady, had checked him in, Boogie found a seat near Nolan and two other friends, chatty Nixie and quiet Vera.

“I already know the sign for I love you,” Nixie announced.

She pointed to her chest with her index finger for I, folded her arms across her heart for love, and then pointed to the others for you.

Boogie didn’t bother to tell Nixie that everyone knew that one and that Nolan probably already knew a hundred signs, maybe a thousand.

“The sign I need to learn is I love dogs,” Nixie went on. “What do you think the sign for dog is?”

Nixie, whose parents wouldn’t let her have a dog, loved dogs more than anyone Boogie knew. Right now Boogie didn’t even like dogs. He still couldn’t forgive Bear for what had happened to Doggie-Dog. Last night in bed Boogie had heard Bing whimpering in his room for half an hour before he finally wore himself out and fell asleep.

“How about this?” Nixie made her hands into little begging paws and hung out her tongue in a panting motion. “Would that be a good sign for dog?”

“Sure,” Nolan said. If Nolan knew the real sign, he didn’t correct Nixie. Boogie sometimes got the feeling Nolan was almost embarrassed at knowing more about everything than everybody else.

“Shush.” Vera, who had been silently doodling in her art notebook, laid down her pencil and put her finger to her lips. “The teachers are going to start talking.”

Vera was the one who cared most about hearing every word every teacher ever said and who worried most if she missed a single instruction.

The teacher standing closer to the door switched the classroom lights off and on three times. The room of campers quieted instantly.

For this camp, both teachers were women. One teacher was short and round with curly hair boinging out all over her head like the springs of an out-of-control jack-in-the-box. The other teacher had long, straight hair that matched her tall, thin body. She was the one who had flicked the light switch.

“I see that worked,” she said with a grin. “If you were a class of Deaf or hard-of-hearing students, I wouldn’t have been able to get your attention by calling out ‘Hey!’ or clapping my hands, right? You’d need a visual cue, and one that didn’t depend on your looking straight at me, either. That’s one of the things you’re going to be learning about Deaf culture this month.”

Maybe Boogie’s mom should try the light-switch trick at home. T.J. and Gib were so used to her yelling they hardly heard it anymore. Or if they heard, they didn’t listen.

“I am Peg,” the tall teacher said, talking with her hands now as well as with her voice. The motions she made with her fingers must have been spelling out her name. “I am hearing.” She moved her index finger in a small circle in front of her mouth.

Peg continued to talk. “This is Sally. She is Deaf.” The shorter, curly-haired teacher placed her finger by her ear and moved it near her lips. That must be the sign for saying you weren’t hearing.

Peg explained that American Sign Language, or ASL, started to develop over two hundred years ago. A man named Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet went all the way to Europe to learn the best way of teaching Deaf students. There, he met a famous Deaf teacher from France named Laurent Clerc. Together, back in the United States, they combined French Sign Language with the signs that Deaf people in America were already using among themselves. This became ASL. In addition to the millions of Deaf people who now communicated through ASL, some parents used sign language with their hearing babies and toddlers who couldn’t speak words aloud yet. It was a beautiful way for anybody to be able to communicate.

The campers were going to start by learning the ASL alphabet. Sign language had the same ABCs as spoken language, but instead of being said out loud, or written on a piece of paper, the letters were formed with your fingers. Sally and Peg explained these were called “handshapes”: the shapes of your hands when they make a letter or a sign.

Sally passed out sheets of paper showing pictures of a hand in twenty-six different positions, one for each letter of the alphabet.

Boogie started to have a bad feeling. Twenty-six of anything was a lot to remember. There were only twelve times tables in math, and Boogie was already stuck on his

sixes. Now he imagined himself stuck on K, or L, or M, while Nolan would know all twenty-six letters after the very first day. Probably Nolan knew all twenty-six letters already.

Just the way Nolan had already known indoor luge was a bad idea.

Just the way Nolan would have remembered to close Bing’s bedroom door.

“We aren’t going to learn every single letter today,” Peg reassured the campers, as if she had been reading Boogie’s thoughts.

Boogie was glad to hear that.

Peg continued, “It will help a lot if you take this paper home and practice the letters for ten minutes every evening.”

Boogie wasn’t glad to hear that.

He already had to practice his multiplication facts, and work on his inventor report for Mrs. Townsend, and walk Bear, and take turns with T.J. for setting and clearing the table. None of the other camps had homework.

The whole time Peg was talking, Sally had been making motions with her hands—probably signing the words for paper and home and practice and ten minutes and every evening.

How would anyone ever learn all those words? And how to put them together into sentences?

Sign language was going to be impossible!

The team of Peg-and-Sally told them to start with the letters for their names. Spelling out a word letter-by-letter was called “finger-spelling.” For finger-spelling, and all signs made with just one hand, you used your dominant hand, the hand you used to write or eat. So as a right-handed person, Boogie would form the letters with his right hand.

Boogie had the longest name in his group, but two of the letters were the same. Luckily, O looked like an O, with fingers and thumb curled to form a circle. The letter I looked like an I, with the pinkie pointed straight up in the air. Some of the other ASL letters looked like themselves, too. For the V in her name, Vera held her forefinger and middle finger apart to form a V. The L in Nolan’s name was forefinger and thumb held in an L shape.

Maybe sign language wasn’t going to be impossible, after all. Though there would still be hundreds—no, thousands—of whole entire words to learn.

Standing Up to Mr. O.

Standing Up to Mr. O. Lucy Lopez

Lucy Lopez Dinah Forever

Dinah Forever Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star

Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star Vera Vance: Comics Star

Vera Vance: Comics Star Izzy Barr, Running Star

Izzy Barr, Running Star You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman

You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman Nixie Ness

Nixie Ness The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish

The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish Basketball Disasters

Basketball Disasters Being Teddy Roosevelt

Being Teddy Roosevelt Losers, Inc.

Losers, Inc. The Trouble with Friends

The Trouble with Friends Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ

Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants

The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants Annika Riz, Math Whiz

Annika Riz, Math Whiz Fourth-Grade Disasters

Fourth-Grade Disasters Pet Disasters

Pet Disasters The Trouble with Ants

The Trouble with Ants Write This Down

Write This Down Alex Ryan, Stop That!

Alex Ryan, Stop That! Kelsey Green, Reading Queen

Kelsey Green, Reading Queen How Oliver Olson Changed the World

How Oliver Olson Changed the World Lizzie At Last

Lizzie At Last Zero Tolerance

Zero Tolerance The Nora Notebooks, Book 2

The Nora Notebooks, Book 2 Cody Harmon, King of Pets

Cody Harmon, King of Pets Fractions = Trouble!

Fractions = Trouble! Makeovers by Marcia

Makeovers by Marcia One Square Inch

One Square Inch