- Home

- Claudia Mills

Pet Disasters Page 6

Pet Disasters Read online

Page 6

Mason wiped it off on his shorts, but more as a matter of principle. After less than a full day with Dog, he was already getting used to dog slobber. He had heard it said that a person could get used to anything. But he knew he’d never get used to carrying dog poop around the neighborhood in a plastic newspaper bag dangling from his hand. Maybe the same person who invented a spitproof dog ball should invent a dog toilet. Probably what really needed to be invented was a new breed of dog that would know how to use it.

But then, what would happen to all the dogs who were here on Earth already, the old-fashioned, poop-on-the-lawn kind of dogs? What if Mason and Brody hadn’t adopted Dog, and Dog had been put to sleep?

Mason’s mom came out of the store carrying a plastic grocery bag. “Got them! Got two, one for each of you.”

Dog jumped up from his resting place on the pavement, thrusting his nose toward the bag, already smelling the treats inside. Mason shoved him away. Even when the bones were safely in the trunk of the car, Dog still seemed excited. His tail, like a huge feathery plume, kept whacking itself against Mason’s face.

Back home, Brody said, “I want to give him my bone first, okay? Then you can give him yours tomorrow. When I’m off on that camping trip.”

What could Mason say? Brody was the one who had thought of getting a bone for Dog, not that getting a bone for a dog was the most original idea in the history of the world.

Dog went wild with joy as the bone was unwrapped, jumping up against Brody, practically knocking him down in his eagerness. Then Dog dragged the bone off into a corner of the kitchen and devoted himself to gnawing it, ignoring both boys equally.

“I love having a dog!” Brody said. “Dog is the best thing that ever happened to me in my whole entire life!”

Mason knew that was saying a lot, because Brody thought everything that happened in his life was wonderful.

Mason didn’t think everything that happened in his own life was wonderful. A lot of things that happened in his life were terrible. But so far, having Dog hadn’t been terrible.

So far, having Dog was pretty nice.

9

Finally it was time for Brody to go home to help his mother and sisters finish packing for their family trip. They were driving to a campground about an hour away to camp for two nights, returning home on Sunday evening.

“Goodbye, Dog!” Brody flung himself on Dog in a farewell hug. “Take good care of him for me, Mason.”

Mason didn’t need Brody to tell him to do that. He might not have wanted a dog, or a cat, or a hamster, or a goldfish, but he had always done his best to take care of them the way he was supposed to, give or take some overfeeding here and there.

Mason went over to Brody’s house with Brody to get instructions for how to take care of Albert the goldfish while Brody’s family was away. He followed Brody up to his room.

Brody’s room was, to put it mildly, messy. His bed wasn’t made. How could somebody not make his bed? Mason shuddered at the thought of getting into a bed that looked like Brody’s: the covers tossed back, the sheet tangled up in a wrinkled ball, the pillow on the floor. Every blank space on every wall was lined with restaurant place mats that Brody had colored, because once Brody colored something with his laborious care, he loved it and would never get rid of it. Every surface of every bureau and bookcase was covered with Brody’s collection of turtles. Not real turtles, thank goodness, but turtles made of pottery, glass, wood, straw. And each turtle had a name.

Mason’s room had nothing on the walls. Now that Goldfish’s bowl and Hamster’s cage were gone, Mason’s room had nothing on top of the bureau and bookcase, and just one monkey-shaped handknit pillow on his bed. There was nothing on the floor except for the rug. Mason didn’t mind the rug. It kept his feet from being cold in the winter before he put on his brown socks.

Amidst all the turtles in Brody’s room sat Albert’s bowl, with Albert’s can of fish food beside it.

“One pinch of food every morning,” Brody said. “So one pinch on Saturday morning, and one pinch on Sunday.”

He showed Mason how many flakes of goldfish food were in a pinch. Mason tried not to blame Brody for being so careful with his instructions.

“Then talk to him for a while, so he doesn’t get lonely. Try talking to him now so he can get used to the sound of your voice.”

“Hi, Albert,” Mason said. He tried to think of something else to say. “I’m the kid who used to have Goldfish. Before Goldfish—well, you know. You were there at the funeral.”

“Albert, Mason is going to be taking care of you while I’m camping,” Brody explained, saying every word slowly and clearly as if Albert would understand him better if he spoke that way.

Albert swam over toward the side of the bowl where the boys were standing. Maybe he really was listening.

Suddenly Brody’s face crumpled. “Oh, Albert, I don’t want to go away and leave you!”

Mason knew Albert wasn’t the only one Brody didn’t want to leave.

“Maybe …” Brody’s face brightened. “Maybe I don’t have to go away! Maybe I can stay with you and Dog at your house!”

Brody tore downstairs to ask his mother. Mason noticed that Brody hadn’t bothered to ask him, Mason, first.

“Can I stay at Mason’s house?” Brody begged as his mother sat on the back porch surrounded by camping gear. “Can I, can I, can I?”

“May I,” she corrected automatically. Then she seemed to realize for the first time what Brody was asking. “No, Brody. This is a family trip. We’re all going.”

“I don’t want to go!”

“But, Brody, you love camping,” Brody’s mom said. “You’ve always loved camping. Albert will be fine with Mason to take care of him. He won’t even know you’re gone.”

It was the wrong thing to say.

“He will, too!” Brody burst out. “Albert loves me! And what about Dog? Dog loves me, too. I just got Dog! I can’t go away and leave him!”

“Mason will take good care of Dog, too. Won’t you, Mason? Dog will be perfectly fine without you.”

This was also the wrong thing to say.

“I won’t go! You can’t make me!”

Mason had never heard Brody say such a thing. Brody never refused to do anything. Brody loved doing everything. Right this minute Brody didn’t sound like Brody.

He sounded like Mason.

Brody came over to Mason’s house to give Dog one last goodbye hug before he went away on the camping trip. He hugged Dog as if he would never let him go. Then he got into the station wagon with his parents and his sisters, and the Baxter family drove away.

Mason had been afraid his parents might expect him to walk Dog all by himself that evening, but instead his dad called for Dog once supper was done, leash in one hand, plastic bag in the other.

“Want to come with me?” he asked Mason.

Mason looked at the plastic bag. He had visions of his father saying, Now you try it.

“I’ll just stay here,” he said.

He did pat Dog a few times later on in the evening and was glad enough to have Dog lying by his feet as he watched TV. But when he went to bed, he made sure to close his bedroom door. He was ready for a good, non-doggy night’s sleep.

Saturday was a glorious day filled with glorious nothing. Mason got up early just for the pleasure of not having to go to art camp. As soon as he came downstairs, Dog came bounding over to him, tail wagging, tongue ready to lick. He jumped up on Mason and tried to lick Mason’s face.

“Down, Dog!” Mason commanded.

Dog obeyed.

“Sit, Dog!”

Dog sat.

Goldfish, Hamster, and Cat had never done anything that Mason had told them to do. Not that he had ever told them to do much of anything.

Mason gave Dog one of the dog biscuits they had gotten at the shelter store. Dog gobbled it up and then licked Mason’s hand. This time Mason didn’t wipe it off on his shorts. It wasn’t worth wiping it off if his parents and Bro

dy weren’t there to see him do it.

After Mason’s standard breakfast of plain Cheerios in a bowl with milk, Mason’s dad appeared with the leash. Dog trembled with happiness at the sight of it.

“Are you up for a walk?” Mason’s dad asked Mason.

“Sure,” Mason said. Maybe dogs didn’t poop in the morning, just in the evening. Or maybe Dog would poop quietly and sensibly when he was out in the yard during the day, and Mason’s parents would deal with it.

There was really nothing like a June morning, the air cool, sprinklers spraying, roses in bloom. Mason held Dog’s leash for the first time. He felt himself as aglow with importance as Brody had been. Mason let Dog sniff everything he wanted to sniff and pee wherever he wanted to pee. His father didn’t tell them to hurry up. He probably did enough hurrying during the workweek at his job organizing road-construction detours.

“Here,” Mason’s father said, to Mason, not to Dog, as they passed one rosebush heavy with huge white blooms. “Smell.”

Mason smelled. Being around Dog made him want to sniff things himself, stick his nose right in and inhale deeply.

Dog didn’t poop on the walk. Apparently morning walks were safe.

Back home again, Dog kept Mason company all day. Whatever Mason wanted to do, Dog wanted to do. If Mason wanted to laze around doing nothing, Dog was glad to do nothing, too, so long as he was by Mason’s side.

When Mason felt like going outside to throw a tennis ball, Dog was beside himself with joy. Mason thought Dog got even better at retrieving during their practice session. Twice, Dog caught a thrown ball right in his mouth. Mason greatly doubted that Dunk’s dog, Wolf, could do that. The wetness of the ball stopped bothering Mason. He pretended it was a ball that had gotten soaked in the sprinkler.

That afternoon, Mason’s parents made him go with them to an African crafts fair held on the library lawn. He didn’t mind going, because Dog came along with them. Neither Mason nor Dog looked much at any of the crafts—lots of colorful clothing that Mason couldn’t imagine ever wearing, lots of enormous pots that must have been made out of humongously long clay snakes. But they had fun, anyway, just being together.

Then it was time for Dog’s evening walk. Dog’s pooping walk? Mason thought about staying at home and saying he was too tired to go—he was too tired to go, as a matter of fact. But Dog looked at him with such longing eagerness that Mason found himself following his dad and Dog out the door.

Thunderstorm clouds were gathering.

“It’s good we’re getting out for the walk before it starts to rain,” Mason’s dad said.

Dog didn’t poop first thing, but then, a block from their house, Dog squatted in that certain way. Mason looked fixedly in the opposite direction.

A minute later, just as Mason had feared, his dad held out the plastic bag and said, “Why don’t you try doing it?”

“Well, you see, Dad, I’m not really a dog-poop person,” Mason explained.

“But what if you need to take Dog on a walk sometime all by yourself?” his father asked.

Wasn’t there some saying about crossing that bridge when you came to it? Picking up dog poop wasn’t something that you had to practice doing, like brain surgery or driving a car. It was something you had to feel like doing, and Mason didn’t feel like doing it right now.

“Mason,” his dad said.

Mason took the plastic bag. He wished he could close his eyes, but then he’d probably miss his aim and squish the poop into an even worse mess. He wished he could hold his nose, but he didn’t think he could perform the operation with only one hand. He wished a lot of things that weren’t going to happen.

Mason slipped the bag onto his hand, the way his father and Brody had done. If they could do it, he could do it. But could he do it and still go on living?

Okay. Okay.

With one quick, sickening motion, Mason reached down and scooped up the poop. An instant later, he had turned the bag inside out and tied it shut.

He was still alive.

At least Mason’s dad took the bag from him. But instead of carrying it himself, he tied it onto Dog’s collar. Mason would have hated walking around carrying a bag of dog poop around his neck, but Dog didn’t seem to mind. Mason had noticed that Dog sniffed as happily at disgusting things as anything else. In fact, one time when they passed something that smelled especially disgusting—Mason didn’t even allow himself to think what it might be—Dog actually tried to roll in it, but Mason yanked him away before he could get anything on his fur.

At bedtime, Mason hesitated before shutting his door against Dog. But he had a feeling that if Dog slept with him once, Dog would sleep with him every night for the rest of his life, and that would be the end of sleep for Mason forever. He thought of Hamster’s noisy wheel, of Cat’s incessant meows.

“Good night, Dog,” Mason said, politely but firmly, and closed his door.

Dog didn’t complain the way Cat had complained. That was another good thing about Dog: Dog was happy when things were good, but Dog didn’t seem sad when things were bad.

Ten minutes later, the first bolt of lightning lit up Mason’s room. A few seconds later came the first deafening clap of thunder.

From outside Mason’s door, Dog gave one low howl. Apparently, Dog did mind when things were bad enough.

The next flash of lightning was even brighter, and the thunder seemed to shake the house.

Dog’s howl grew even louder.

Mason didn’t like thunder himself. When he had been afraid of lightning and thunder, back when he was little, his mother had told him that thunder was the sound of the angels bowling up in heaven. Mason hadn’t believed her. He couldn’t picture angels, with their wings and halos, having a raucous evening out in a bowling alley.

Crash! Some angel somewhere had bowled another strike, or maybe the entire angel bowling team had bowled strikes in each lane simultaneously. Either that, or the lightning was about to strike Mason’s house and they were all going to die. The second explanation struck Mason as more likely, more in keeping with the laws of natural science.

This time Dog wouldn’t stop howling. There were times when animals were smarter than humans. No animal would fall for a story about bowling angels.

Mason climbed out of his covers and opened his door. He had thought Dog would dash into his room and dive under the bed, but instead Dog leaped up on top of the bed, as if he knew that was where he was supposed to be all along.

Mason crawled back into bed next to him. The bed was just wide enough for the two of them if they lay very close together. He hugged Dog tight.

“It’s okay,” Mason told Dog, putting on his most calm and soothing voice.

Actually, it was okay. Somebody who survived picking up dog poop could probably survive a thunderstorm. Especially if he had a strong, warm, smart, loving Dog there beside him.

10

Sunday evening, Brody returned. The Baxter station wagon pulled into the driveway around seven o’clock. Brody dashed out of the backseat of the car, where he had been sandwiched between his sisters, and raced over to Mason’s yard to join Mason and Dog, who were sprawled on the lawn side by side under the shade of a big oak tree.

Dog bounded up to greet him, and Brody was down on his knees with his arm around Dog, hugging him tight.

“Look, Dog! I brought you some presents!”

Brody picked up the pinecone and two sticks that he had flung on the grass when he gave Dog his hug. He held them so that Dog could sniff them.

“For playing fetch!”

Dog seemed to like the presents. He gave Brody’s face a huge lick.

Mason’s heart hurt. Brody hadn’t been the one lying beside Dog during the thunderstorm. Brody hadn’t been the one keeping Dog safe all night long.

Dog wasn’t too interested in the pinecone. When Brody threw it, Dog went obligingly to look for it, but didn’t bother bringing it back.

Mason gave a small smile. Maybe Brody’s presents

weren’t so wonderful, after all.

But Dog did like the new sticks. Probably he would have liked any sticks. When you got right down to it, a stick was a stick, and there wasn’t much to distinguish one stick from another.

The three of them played fetch with the new sticks until dark. Brody took a turn throwing, then Mason, then Brody, then Mason. Dog retrieved both boys’ tossed sticks with equal energy and enthusiasm.

Cammie and Cara came over and played for a while, too, giggling when either one hurled an especially wild throw, and making a huge fuss over Dog every time he dropped a stick at their feet.

“Did you ask your mother about Nora? Coming over?” Brody asked when it was almost dark and Mason had to slap away the first mosquito.

“I forgot,” Mason said truthfully.

“I want everybody in the world to get to play with Dog!” Brody said.

Mason didn’t.

Finally, after two more last tosses, Brody said, “Well, I guess I’d better go home and say hello to Albert.”

Albert!

In the fun of playing with Dog all weekend long, Mason had forgotten not only all about Nora, but all about Albert. He had forgotten about him completely.

He hadn’t gone over to Brody’s house to talk to Albert so Albert wouldn’t be lonely.

Worse, he had forgotten to feed Albert. He hadn’t given him even one pinch of carefully measured fish-food flakes.

Albert was probably dead. As dead as Goldfish—not from overfeeding but from underfeeding, or in other words, starvation. Albert was probably dead, and it was all Mason’s fault.

Should Mason tell Brody right now, or let Brody find out on his own? Should he go over to Brody’s house with him, to be by his side when he found out, or wait to hear the distant sound of Brody’s heartbroken wail?

“I’ll go with you,” Mason said.

If he had been Brody, that comment would have made him suspicious. But Brody wasn’t the suspicious type.

Mason followed Brody’s quick footsteps into the Baxter house, past the heaps of camping gear lying in the front hall, and up the steps to Brody’s room, where he was sure they would see Albert’s small orange body floating lifeless on top of the water in an all-too-familiar way. And then he would say—what would he say? What could he say?

Standing Up to Mr. O.

Standing Up to Mr. O. Lucy Lopez

Lucy Lopez Dinah Forever

Dinah Forever Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star

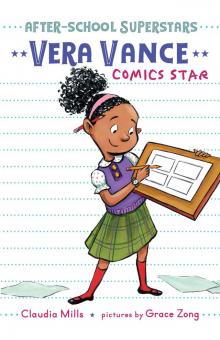

Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star Vera Vance: Comics Star

Vera Vance: Comics Star Izzy Barr, Running Star

Izzy Barr, Running Star You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman

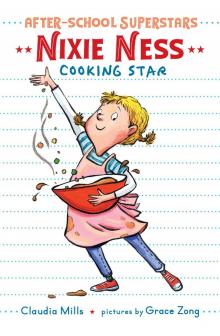

You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman Nixie Ness

Nixie Ness The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish

The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish Basketball Disasters

Basketball Disasters Being Teddy Roosevelt

Being Teddy Roosevelt Losers, Inc.

Losers, Inc. The Trouble with Friends

The Trouble with Friends Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ

Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants

The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants Annika Riz, Math Whiz

Annika Riz, Math Whiz Fourth-Grade Disasters

Fourth-Grade Disasters Pet Disasters

Pet Disasters The Trouble with Ants

The Trouble with Ants Write This Down

Write This Down Alex Ryan, Stop That!

Alex Ryan, Stop That! Kelsey Green, Reading Queen

Kelsey Green, Reading Queen How Oliver Olson Changed the World

How Oliver Olson Changed the World Lizzie At Last

Lizzie At Last Zero Tolerance

Zero Tolerance The Nora Notebooks, Book 2

The Nora Notebooks, Book 2 Cody Harmon, King of Pets

Cody Harmon, King of Pets Fractions = Trouble!

Fractions = Trouble! Makeovers by Marcia

Makeovers by Marcia One Square Inch

One Square Inch