- Home

- Claudia Mills

Basketball Disasters Page 6

Basketball Disasters Read online

Page 6

With twelve seconds left, the score was still tied: 20–20. The Y didn’t allow fourth-grade games to go into overtime, so if no one scored in the next twelve seconds, the game would be recorded as a tie.

The ball went out of bounds. Brody took the ball for the in-bounds pass. From the bench, Mason saw him scan the court, looking for an open player.

The only person open was Dylan. The other team seemed to have given up on guarding him, apparently viewing him as a random kid in a yellow T-shirt who had wandered aimlessly out onto the court but wasn’t really part of the game.

Brody passed to Dylan.

The ball bounced off Dylan’s chest. He grabbed it and made the worst shot in the history of basketball. The ball went straight up, two pathetic feet, nowhere near the basket, proving that there was no need for a green-shirted player to waste any time guarding Dylan.

Julio was on the ball in a flash, hurling it toward another kid who was in position to score.

Fwee! The ref blew his whistle to signal the end of the game. The Fighting Bulldogs had lost 22–20.

Because of Dylan.

No. Because of Brody.

9

“Terrific game, team!” Coach Dad said, after the team handshake, during which Mason was once again able to avoid any actual finger-to-finger contact with the other players.

Terrific game? Had his father failed to notice that the Fighting Bulldogs had lost?

“What a difference from last week!” Coach Dad went on.

Mason had to admit that having players who knew how to play had been a definite improvement.

As if reading Mason’s thoughts, his dad said, “It was great having a full roster, wasn’t it? But you original Bulldogs have also improved by leaps and bounds.”

Except for Dylan, who couldn’t have made a leap or a bound if his life depended on it.

How could Brody have passed to Dylan?

Mason stalked past Brody and his family on the way out to the parking lot. He was so mad that it was better to avoid Brody altogether than to say anything right now.

But Brody caught up with him. “I made us lose,” Brody said in a small voice.

Correct!

Mason’s dad laid a hand on Brody’s slumped shoulder. “I told you all to pass to someone who was open. Dylan was the only one open. Nobody else passed to Dylan for the entire time he was in the game. So you did a kind thing, Brody, to make Dylan feel like he’s truly part of our team.”

Part of our losing team.

Brody’s face brightened. Brody was incapable of staying sad for very long. “I bet we win next time!”

“I bet so, too,” Coach Dad said.

Mason didn’t say anything.

By the next practice, Mason had forgiven Brody. He and Brody had been best friends since Little Wonders Preschool. Mason wasn’t going to stop being best friends with Brody because of one basketball game. Besides, he wasn’t as mad at Brody for a bad pass as for having talked him into playing basketball in the first place, and so far Mason had managed to forgive Brody for that.

This is going to be great! Ha!

The colonial craft that week was writing “mottoes”—inspirational sayings—on parchment with a cartridge pen filled with real ink. Colonial people would have used a quill pen made out of a feather, and they would have made their ink out of crushed berries.

Brody, Nora, and Mason all wrote Ben Franklin sayings.

Brody wrote, “Early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.”

Nora wrote, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

Mason wrote, “The worst wheel of a cart makes the most noise.”

In Coach Joe’s class the worst and noisiest wheel, in Mason’s opinion, was Dunk. Dunk’s cartridge pen kept blotting. After fifteen minutes, Dunk had ink on his fingers, his nose, even one ear. Sheng laughed at Dunk, and Dunk threatened to smear ink on Sheng. The American Revolution would have broken out all over again if Coach Joe hadn’t stepped in to make peace.

On Saturday the Fighting Bulldogs lost their third game in a row, 24–18. Mason had almost scored a basket in the third quarter—the ball had teetered on the rim so long that Brody was already slapping him on the back in congratulation. And then, as if by doomed magic, the ball had refused to go in.

“But look how close we’re getting,” Coach Dad told the team when they all went out for pizza afterward.

Mason didn’t bother to point out that the score had actually been closer the game before, so that technically they were getting worse, not better. He focused on the thought that in a few more weeks, basketball season would be over forever.

Thanksgiving break stretched ahead—long, delicious days with no school, no basketball practice, no basketball game, undisturbed time to hang out with Dog from morning to night.

So long as Dog didn’t place any one of his three paws on Mrs. Taylor’s lawn.

Mason still had never laid eyes on Mrs. Taylor in the flesh. All he had seen of her was a blurry face at the upstairs window. But he had a good image of her in his mind: toothless—no, maybe with one blackened tooth to make her look like a jack-o’-lantern—a beaked nose—wild, staring eyes—wisps of uncombed white hair—a black peaked hat.…

What if Mrs. Taylor had moved next door, not to a kind, gentle, wonderful dog like Dog, but to a barking, biting dog like Dunk’s dog, Wolf? Last summer, Wolf had attacked Dog and injured him so badly that Dog had had to go to veterinary urgent care. How would Mrs. Taylor like living next door to a dog like that?

On the afternoon before Thanksgiving, Mason was out in the driveway dribbling up and down with Brody and Dog.

“Are you going somewhere tomorrow? For Thanksgiving?” Brody asked. “I’m going to my grandparents’ house.”

Mason shook his head. All his relatives lived far away, and no one in his family felt like flying on a busy holiday weekend. So he and his parents and Dog would have their own little Thanksgiving dinner at home. Mason was glad that his mother always made normal holiday food for Thanksgiving—turkey, stuffing, cranberry sauce, sweet potatoes. But then she did strange things with the leftovers. Pakistani turkey curry had been the worst, as Mason recalled.

Brody gave Dog one last hug, and both boys went inside.

The phone was ringing as Mason came into the house. His mother picked it up.

“Who is this, please? … Oh, Dunk.… How is your finger? … I’m glad.… Yes, he’s right here.”

She handed the phone to Mason, who stared at it as if it were under some kind of enchantment. Dunk had come to the house once, to give Dog a present after Dog got hurt by Wolf, but he had never called Mason on the phone.

“Hello?” Mason said cautiously into the receiver.

“My parents made me call,” Dunk said, by way of beginning the conversation.

Mason waited to hear exactly why Dunk’s parents were making him do this.

“The stupid report? On stupid Ben Franklin? I can’t find my stupid library book.”

Mason thought about asking, Whose stupid fault is that? but he didn’t.

“And all the Ben Franklin books are checked out of the public library, and Coach Joe said we have to use real books and not the Internet, and the report is due next week, and I haven’t started it yet, so my parents said I have to work on it over the break, and my book disappeared, and they said I have to call someone else who is doing Ben Franklin and borrow their book for a couple of days, and so I called you.”

Mason wondered if he should be flattered that Dunk called him and not Nora or Brody.

“I tried to call Nora and Brody, but nobody at their houses answered the phone,” Dunk added. “So can I? Borrow your book? I promise I won’t lose it.”

Mason hesitated before he replied. Dunk didn’t exactly have a stellar track record with library books.

“Okay,” he said finally. After all, his report was almost done, so it seemed mean not to loan the book to Dunk.

“Can I

come over now and get it?” Dunk asked. “I have to take Wolfie for his walk, anyway.”

“Sure,” Mason said. “Yeah, come when you walk Wolf.” He couldn’t bring himself to say “Wolfie.”

He could just hand Dunk the book, close the door, and walk away.

Copying Mrs. Taylor, Mason watched from his window for Dunk and Wolf. He heard Wolf barking even before he saw the two of them coming down the street. Dunk was strong, but he was clearly struggling to hold on to Wolf’s straining leash.

Mason shrugged on his jacket. Dog jumped up to follow him.

“No, Dog. You have to stay here.” Mason wasn’t about to allow Wolf to harm Dog again, ever.

Dog gave a little whimper of disappointment, but then let Mason lead him into the kitchen for a dog biscuit and a hug.

Leaving Dog behind in the kitchen, Mason opened the front door as Dunk and Wolf cut across the lawn to where he was standing.

“Hey, Dunk,” Mason said.

“Hey,” Dunk said.

Wolf growled a greeting.

“Are you ready for us to cream you again?” Dunk asked.

There were six games in the fall basketball season, and six fourth-grade teams, so the final game was to be a rematch between the Fighting Bulldogs and the Killer Whales.

Mason shrugged. Maybe Dunk didn’t yet know that Nora and her friends had joined the team.

“Forty-three to eight,” Dunk said. “I mean, I’ve heard of slaughters, but forty-three to eight?”

The pleasant conversation had gone on long enough; it was time for Mason to hand Dunk the library book and send him on his merry way. But busy with attending to Dog, Mason had left the book inside the house on the little table by the front door.

Mason opened the door quietly, hoping Dog wouldn’t hear him and come dashing to his side. Luckily, Dog seemed still to be in the kitchen. Dunk crowded in behind Mason, without Wolf, thank goodness.

“There’s the book,” Mason said, pointing.

Instead of taking the book, Dunk picked up Dog’s tennis ball, which lay on the table next to it.

“Is this for your freak dog?” he asked. “How can he catch a ball with only three legs?”

“He can catch better than Wolf!” Mason retorted.

“No, he can’t! Wolf can catch ten thousand times better!”

The next thing Mason knew, he was outside again with Dunk and Wolf. Dunk unclipped Wolf from his leash and gave the ball a good hard throw.

Right into the Taylors’ yard.

Wolf raced over to get it, as if it had been a freshly killed bird or squirrel.

“Um—” Mason said. “The lady next door? She doesn’t like dogs.”

But he had to admit he didn’t say it very loudly.

Dunk threw the ball even farther the next time. Again Wolf darted into the Taylors’ yard to retrieve the ball, barking his deep, savage bark.

Out of the corner of his eye, Mason glanced toward the Taylors’ upstairs window. The curtain was pulled back.

Then, ball in mouth, Wolf apparently remembered that there was some other business he hadn’t taken care of yet on his afternoon walk. Still on the Taylors’ side of the property line, Wolf carefully squatted and took a nice long time doing a massive poop.

“Do you have a plastic bag with you?” Mason asked Dunk.

Dunk looked puzzled.

“To clean it up? To pick up Wolf’s poop?”

Dunk made a retching sound. “Are you kidding? That’s disgusting!”

As if it weren’t disgusting to let your dog poop on someone else’s lawn and then leave it there.

Mission accomplished, Wolf trotted back with the ball and dropped it at Dunk’s feet. Dunk threw the ball again, so hard that it landed in the lawn on the other side of the Taylors’ house.

“I bet you can’t throw as far as I can,” Dunk said.

“Wow, Dunk,” Mason said. “You do throw far. But you’d better be careful. I think there’s a law against letting your dog run into other people’s yards.”

Dunk wouldn’t be able to say he hadn’t been warned.

“Yeah? What are they going to do about it?” Dunk demanded.

Dunk kept throwing the ball for Wolf, farther and farther. Wolf kept sprinting to get it, barking, barking, barking.

A familiar-looking panel van pulled up in front of Mason’s house.

A familiar-looking animal-control officer got out.

“Hey, kids,” he said. But he wasn’t smiling this time. “I warned you boys to keep your dog off the neighbor’s property.”

Then he looked more closely at Dunk, who obviously wasn’t Brody, and at Wolf, who obviously wasn’t Dog.

“My dog is in the house,” Mason said innocently. “This is my friend’s dog.”

Well, my enemy’s dog.

“I told you to be careful,” Mason said to Dunk, trying to make his voice sound irritated.

“Your neighbor reported that not only did you let your dog run wild in her yard with no effort to control him, but you failed to clean up after him,” the animal control man continued. “Is that correct?”

“Yes, sir,” Mason said, before Dunk could deny it. Now he tried to make his voice sound ashamed. “We’re sorry, sir.”

“I’m afraid ‘sorry’ isn’t good enough this time,” the man said.

From his pocket, he handed Mason a plastic bag.

Mason handed it to Dunk.

Mason was used to picking up dog poop now, but he remembered how sick he had felt the first time he had to do it. And he hadn’t even had an animal-control officer watching to make sure he did it correctly.

“I’m going to have to write you a ticket,” the man told a green-faced, gagging Dunk, who had returned with a lumpy plastic bag in his hand.

Both boys stood silent as the man took his time filling out the ticket and then handed it to Dunk. “You give that to your parents, you hear?”

“Yes, sir,” Dunk mumbled.

It occurred to Mason to be relieved that his own father was out running errands, and his mother was lost in her editing work in her office upstairs at the back of the house.

Then the man got into his van and drove away.

“This stinks!” Dunk burst out.

Mason didn’t know if Dunk was talking about the poop-filled bag he was holding in one hand or the ticket he was holding in the other hand. Or both.

“My dad is going to kill me!”

Mason gave a small cluck of sympathy.

“Well, Wolf can fetch a million times better than Dog! And the Killer Whales are going to slaughter you guys again!”

With that, Dunk dropped the bag, clipped Wolf’s leash back on, and stalked away.

Mason saw that Dunk had forgotten the bag of dog poop.

And the Ben Franklin library book.

10

Mason stood on the sidewalk, feeling strangely satisfied. Was it Ben Franklin who had said you could kill two birds with one stone?

The saying meant that you could accomplish two things in one fell swoop. For example, even though Mason hadn’t planned it that way, you could get even with a nasty old dog hater and with a boy who bragged too much about basketball, all by being willing to loan a library book.

When Mason went into the house after tossing the poop bag in the trash, the phone was ringing.

It was far too soon for it to be Dunk, realizing that he had failed to get the one thing that had been the reason for his disastrous visit.

Of course, it could be—

“Mrs. Taylor!” Mason heard his mother say into the phone as she was bustling around in the kitchen getting ready for dinner.

Mason didn’t stick around to hear any more. He and Dog fled to the safety of their bedroom.

A few minutes later, his mother pushed open his door. Mason and Dog were lying side by side on Mason’s bed.

“Mason,” she said in her best disappointed-sounding voice.

“It wasn’t my fault! Dunk came to get a book

for school, and he had Wolf with him, and you know what Dunk is like! And what Wolf is like! I told him about Mrs. Taylor. But he didn’t listen!”

“Yes,” his mother said sternly. “I know what Dunk is like, and you do, too. Mrs. Taylor said you played together for half an hour and Wolf repeatedly ran into her yard and did his business on her grass.”

“I told Dunk to clean it up!”

“Did you clean it up? Dunk and Wolf were here as your guests.”

“I didn’t invite them. They invited themselves!”

“Mason, Mrs. Taylor was distraught. Do you know what ‘distraught’ means? Extremely, extremely upset. She has high blood pressure. She has a heart condition. It is very dangerous for her to get so upset. And I cannot believe that you honestly thought Wolf’s behavior wouldn’t upset her or that you made any serious effort to stop it.”

Mason buried his face in Dog’s soft fur. Okay, he did feel awful now. He didn’t want to make even a spying dog hater have a heart attack and die. Mason had his faults, but he wasn’t a cold-blooded old-lady murderer.

“What should I do?” Mason asked his mom, his voice muffled.

“You need to apologize to Mrs. Taylor.”

Mason could write her a note in his best cursive. His mother was big on handwritten thank-you notes for birthday and Christmas presents. Maybe she’d think a handwritten apology note would be a good idea.

“I felt so sorry for the Taylors,” she went on, “that I invited them to join us for Thanksgiving dinner tomorrow. So you can apologize to her in person then.”

What?

“But—what about Dog? She hates dogs!”

“Dog, I’m afraid, will not be able to have dinner with us. Dog will have to be in the basement.”

“But—this is Dog’s first Thanksgiving at our house! Dog can’t miss Thanksgiving!”

“Mason, from Dog’s point of view, Thanksgiving is just another day. You can make it up to him with a nice bone.”

“But he’ll think he did something bad! And he didn’t do anything!”

Standing Up to Mr. O.

Standing Up to Mr. O. Lucy Lopez

Lucy Lopez Dinah Forever

Dinah Forever Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star

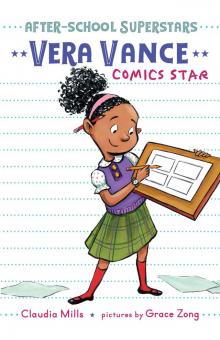

Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star Vera Vance: Comics Star

Vera Vance: Comics Star Izzy Barr, Running Star

Izzy Barr, Running Star You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman

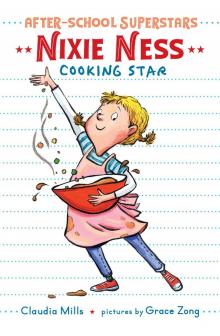

You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman Nixie Ness

Nixie Ness The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish

The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish Basketball Disasters

Basketball Disasters Being Teddy Roosevelt

Being Teddy Roosevelt Losers, Inc.

Losers, Inc. The Trouble with Friends

The Trouble with Friends Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ

Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants

The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants Annika Riz, Math Whiz

Annika Riz, Math Whiz Fourth-Grade Disasters

Fourth-Grade Disasters Pet Disasters

Pet Disasters The Trouble with Ants

The Trouble with Ants Write This Down

Write This Down Alex Ryan, Stop That!

Alex Ryan, Stop That! Kelsey Green, Reading Queen

Kelsey Green, Reading Queen How Oliver Olson Changed the World

How Oliver Olson Changed the World Lizzie At Last

Lizzie At Last Zero Tolerance

Zero Tolerance The Nora Notebooks, Book 2

The Nora Notebooks, Book 2 Cody Harmon, King of Pets

Cody Harmon, King of Pets Fractions = Trouble!

Fractions = Trouble! Makeovers by Marcia

Makeovers by Marcia One Square Inch

One Square Inch