- Home

- Claudia Mills

Losers, Inc. Page 3

Losers, Inc. Read online

Page 3

“Sure,” Julius said. “We can do our own projects. Whatever you want.”

“Just this once,” Ethan said lamely.

“It’s okay. I understand,” Julius said in a tone that made Ethan wonder whether Julius didn’t understand, or whether Julius understood too well.

Four

“How was school today?” Ethan’s mother asked that night at dinner.

“Fine,” Peter said.

“Fine,” Ethan said.

“Did anything interesting happen to either of you?”

“No,” Peter said.

“No,” Ethan said. But he felt a little sorry for his mother, making doomed efforts every night to generate some family dinner conversation. Family dinners were important to her—real dinners where everyone ate the same thing, instead of foraging in the fridge for snacks. And where people talked to each other instead of gobbling their food in silence.

“We got a student teacher in science,” Ethan said.

His mother gave him a grateful smile. “What’s he—she?—like?” His father looked up from his plate. Ethan’s dad wasn’t much of a talker, but he was always a good listener.

“It’s a she. She’s nice.”

“Long hair?” Peter asked. Ethan nodded. “I saw her in O’Keefe’s room. Is Zimmerman in love with her yet?” Julius’s crushes had become a family joke.

“Uh-huh.” Ethan felt his own cheeks flushing and hoped no one else noticed.

“What about you, Peter?” his mother asked. “Did you tell your math teacher about your letter from Representative Bellon?”

“No,” Peter said. He ate another forkful of casserole. Then he relented, too. “The game this Friday? Coach Stevens invited Coach McIntosh from the high school to see us play.”

“You mean to see you play,” his mother said, refilling Peter’s milk glass from the pitcher on the table.

“Well, he didn’t say that. But I think—I know he hopes I’ll do a good job.”

“Of course you will!”

“Just do your best,” his father said. “That’s all anyone can ever ask of you.”

“I got a new child in my class,” Ethan’s mother said then. Since she was the only member of the family who liked to talk, most of the Winfield dinner conversations centered on the activities of three-year-olds at the Little Wonders preschool. Ethan couldn’t remember his father ever telling a story from his carpet-cleaning business.

“Edison,” she went on. “That’s his name. Edison Blue. Very negative. His mother couldn’t get him to come inside this afternoon when she was dropping him off. ‘You’ll be all cold and wet,’ she told him. ‘I want to be all cold and wet,’ he said. When she finally carried him in, kicking and screaming, he ran right back outside again and stood in the exact same spot where he had been standing before.”

“What did you do?” Ethan’s dad asked. “I’d have been tempted to leave him there.”

“Well, I finally got his mother to go. You can’t do anything with them when their mothers are there. And then he came in after a while, when he saw that I wasn’t overly impressed by his little tantrum. But I can tell that Edison Blue is going to be an interesting addition to Little Wonders. Do you boys have much homework to do?”

“Not tonight,” Peter said. “I thought I’d get started on the science fair.”

“Me too,” Ethan said. He hoped he wasn’t blushing again. Quickly he began clearing the table, just in case.

* * *

Upstairs in his room, Ethan tried to think of a project for the science fair, but he didn’t know how to begin. In elementary school, he and Julius had just done whatever project their dads suggested, from a library book Ethan’s mother checked out every year on award-winning science fair ideas. One year they had done something with magnets. Another year they had let mold grow on different foods: apples, bread, yogurt. That had been Ethan’s favorite project. He forgot what their hypothesis had been, but he still remembered how gross the food had looked when the project was displayed in the elementary-school gym.

This year he wanted to do something different—not an experiment out of a book but one he thought up all by himself. He wanted the judges to be astonished that a twelve-year-old boy could have thought up such a project and carried it out all alone, single-handedly pushing back the frontiers of science. He wanted to be the youngest person ever to win a Nobel Prize. And when he did win, he’d say in his acceptance speech, “Everything I am today I owe to my sixth-grade student teacher, Ms. Grace Gunderson.” And she would shake back her golden hair and smile at him the way she had in class today.

So Ethan knew that he wanted his project to win the Nobel Prize. The problem was, he still didn’t have the faintest idea what the project should be.

* * *

As he biked to school the next day, Ethan wondered if Julius would still be mad at him. Not that Julius had acted particularly mad after the conversation about the science fair. They had watched dumb cartoons together, as they usually did. They hadn’t talked much; they usually didn’t talk much. But this time the silence had felt different.

Julius was on the playground first. Ethan made himself go up to him.

“Hey, Veep,” Julius said, punching his shoulder.

“Hey, Prez,” Ethan said, punching him back. It was good to know that Losers, Inc., was still going strong. Or as strong as it could be with its vice president breaking its rules.

“I saw her drive into the parking lot,” Julius said then, lowering his voice to the lovesick sigh he used whenever he talked about Ms. Gunderson. “That’s her silver Honda Accord over there. See it? Next to the red Jeep Cherokee.”

Ethan glanced over at it dutifully. He was in love with her, too, maybe even more in love than Julius was, but he didn’t feel any particular thrill from seeing her car. People must fall in love in different ways. He didn’t want to talk about her, either, the way Julius did. He just wanted—it sounded corny, but it was true—to do some great deed that would be worthy of her. But so far the only great deed he could think of was winning the science fair.

In first-period science, Ms. Gunderson again gave the class time to work on their projects. Most kids were working in groups of two or three, so all around the room they were busy pulling their desks together. Ethan sat alone. So did Julius. Ethan hoped some kids would invite Julius to join their group. No one did. He and Julius had worked together so many times, yet no one seemed to notice that today Julius’s only partner had abandoned him.

Once again Ms. Gunderson circulated from group to group, talking over everyone’s ideas. As she sat with Marcia’s group, right next to him, Ethan stared at her instead of at the blank page on which he had written SCIENCE FAIR IDEAS so hopefully last night. Her hair was up, in a long braid twisted around her head. It made her look foreign—Swedish, maybe. She wore a purplish dress today, as long and swirly as her skirt had been yesterday.

She was standing up. She was turning away from Marcia’s group. She was coming toward him. She was pulling up an empty chair next to his.

“Ethan,” she said in her low voice.

She remembered his name.

Ethan tried to make his face look mature and intelligent, the thoughtful face of a future scientist.

“Have you had a chance to think any more about the science fair project?” she asked him.

Only every minute since nine-thirty yesterday morning.

Ethan nodded. He laid his arm over his blank paper, to hide its blankness. “I have a few ideas I’m working on, but they’re still pretty rough.”

Ms. Gunderson didn’t get up to go on to the next group. She sat patiently. Her expectant silence invited Ethan to say more.

“I sort of wanted to do something … different,” Ethan said finally.

“Different?”

“My mom has this book on science fair projects—it’s a library book, really—but I didn’t want to do another one of the experiments from the book.” I want to do an experiment that will

win the Nobel Prize. He didn’t say it. He couldn’t meet her eyes.

“That’s wonderful, Ethan,” Ms. Gunderson said softly. “I’ve found that ‘different’ experiments are usually the best. And I know it’s a lot harder to come up with something of your own. I think the secret is to start with a problem that interests you. Start by making a list of some things you really care about.”

“Um, sports, I guess.”

As soon as he had said it, he hated himself. Sports! He sounded as idiotic as Barnett yesterday, stammering about “wires and stuff.” He wanted to sound like Einstein or Sir Isaac Newton, not like a dumb sports nut—worse, a dumb sports nut who wasn’t even good at sports.

“Ethan.”

He made himself look up, but not directly at her face.

“The human body in motion is a fascinating subject for science. There are hundreds—thousands—of exciting scientific questions that have to do with sports. I know you’ll find one that will make a wonderful science fair project.”

She smiled at him and he smiled back, catching her enthusiasm like a softball dropped from the sky overhead into his waiting glove.

Then she was gone, off to Lizzie’s desk. Lizzie was the only kid besides Ethan and Julius who was working alone.

Could you win a Nobel Prize for discovering something about sports? Ethan didn’t know. But he was determined to find out.

* * *

During study hall, Ethan made some more entries in Life Isn’t Fair: A Proof. If he kept going at this rate, before the year was out he would have written a book longer than A Tale of Two Cities.

Tuesday, January 28. In art class, everybody’s pots were fired in a kiln. Ethan Winfield’s pot was the only one that cracked. Ms. Neville told him, “These things happen.”

Tuesday, January 28. During math class, Ethan Winfield’s PAL partner wrote a whole entire poem called “Ode to Winter.”

That night the Winfields had spaghetti and meatballs for dinner. Ethan was starving. Being in love seemed to give him an appetite.

“How was school today?” Ethan’s mother asked.

“Fine,” Peter said.

“Fine,” Ethan said.

“Just ‘fine’? Nothing wonderful? Nothing terrible?”

Peter shook his head. Ethan did, too.

Tonight Peter gave in first. “At practice after school this afternoon, Coach Stevens took me aside and told me—well, he does want Coach McIntosh to know that I’ll be coming up to Summit High next year and, you know, to be kind of on the lookout for me.”

“That’s great, son,” Ethan’s dad said.

“I just wish I were taller,” Peter said.

Peter wished he were taller? If Ethan could ever be five foot six, he would never again ask for anything.

“You’re still growing,” Ethan’s mom said. “Both of you are still growing.”

“How’s Edison Blue?” Ethan asked, to change the subject.

“The same. Today Troy Downing brought in his pet dog, Winkles, for sharing time, and Edison told Troy that Winkles was not a dog. The more Troy insisted that Winkles was a dog, the more Edison insisted that he was not a dog. The two of them actually came to blows over it.”

“Who won?” Peter asked.

“Well, I put a stop to the punching right away. But Edison never backed down. Don’t go away, there’s apple crisp for dessert.”

As she was serving the crisp, she said to Peter, “You’re not worried about Friday night, are you?”

“Not really,” Peter said. “Maybe a little bit.”

“Don’t worry,” she told him. “Just play the way you always do.”

In other words, Ethan thought, just be perfect. And of course Peter would be, as always, and Coach McIntosh would be astonished by Peter’s wonderfulness, as all grownups always were, and next year Peter would be as big a star in high school as he had been all through middle school. At least Ethan wouldn’t have to witness it all firsthand.

Five

By Wednesday, Monday’s snow had mostly melted. There was still enough snow in shady patches for Ethan and Julius to use in a quick snowball fight on the way home from school, but most of the lawns were bare.

Julius had to go to his orthodontist appointment, so they couldn’t have an after-school meeting of Losers, Inc. Instead, Ethan shot baskets in his driveway all alone. He tried lay-up after lay-up until the muscles in his arms and shoulders began to ache. It was a good kind of ache, the satisfying soreness of muscles training themselves to do what they were supposed to do.

Then Ethan dribbled up and down the driveway as fast and hard as if he were driving down the court with the other team’s guards in hot pursuit. The impact of his hand against the ball, the rhythm of the ball rebounding from the pavement, the tingling warmth in his forearms—it all felt great.

The ball bounced obediently under his hand, as if some force in the ball were responding directly to the force in his cupped fingers. Bounce. Bounce. Bounce. Bounce. Ethan felt like a bouncing machine, programmed to keep on bouncing the ball in the same unchanging rhythm forever. Bounce. Bounce. What made a basketball bounce the way it did? Why was it bouncier than a soccer ball, even though both were about the same size and shape? And those tiny little super-balls. Why did they bounce so hard and so high?

Ethan caught the ball on its next up-bounce. He had it! He had the question for his science fair project. He would test all different kinds of balls, bouncing on all different kinds of surfaces, to try to find out which balls bounced the highest and why. He knew it wouldn’t win a Nobel Prize, but he had thought it up all by himself, and it had come out of a real question that really mattered to him, just as Ms. Gunderson had said it should. He could hear her voice right now, telling him, “Why, Ethan, what an original idea! I knew you’d come up with something wonderful!”

* * *

On Thursday morning, they didn’t have class time to work on their projects, but Ethan made himself go up to her after class. She was wearing a tight-fitting top, the kind that dancers wear, and the same skirt she had worn on the first day Ethan had ever seen her. Her hair was down, held back from her face by two glistening silver barrettes.

“I have kind of an idea for my science fair project,” he told her.

“What is it?” she asked, as if there were nothing in the world she wanted to know more.

And when he told her, sure enough, she said, “Ethan! It’s perfect for you. I knew your interest in sports would lead you to something wonderful.”

Even Peer-Assisted Learning couldn’t spoil Ethan’s happiness. He felt so good that for the first time he tried to pay attention to Lizzie’s long, breathless explanations of the day’s new batch of math problems.

During study hall that day, Ethan actually studied. He wasn’t going to be able to finish all 422 pages of A Tale of Two Cities in fourteen days unless he forced himself to read at least 30 pages—30 whole entire pages—every single day, including weekends. He was up to page 90 so far. If he had picked the 103-page book about a dog that Julius had found for him, he would be almost finished by now. Except that he wouldn’t have started it yet. He and Julius always put off reading their book-report books until the night before the book reports were due.

A Tale of Two Cities wasn’t the best book Ethan had ever read, but it wasn’t the worst, either. It took place during the French Revolution, in the 1700s. Once Ethan realized that Madame Guillotine was a special machine for cutting off heads, the story became considerably more interesting. They were a pretty bloodthirsty bunch, those French Revolutionaries.

Ethan could tell that his reading during study hall annoyed Julius. Sitting next to him, Julius fidgeted. He started another batch of doodles of Ms. Gunderson. The point on his pencil broke. He sighed heavily. Then he trudged off to sharpen his pencil.

When Julius returned to their table, he whispered to Ethan, “You’re really going to read the whole thing?”

Ethan nodded. He was going to read the whole thing, eve

ry single, solitary page. He didn’t know how to explain his determination to Julius.

“I have to.” He heard Ms. Leeds’s voice again in his head: “I have to say that it is very disturbing…” But he didn’t feel like letting Julius see how much the teacher’s comments had bothered him. Instead he said, “It’s my revenge against the Lizard. When she sees I’m reading a longer book than she did, she’ll die. She always reads the longest book of anyone in the class. This time she won’t.”

“It’s not worth it,” Julius said. “I wouldn’t read 422 pages to stop someone from blowing up the world.”

The librarian, Ms. Dworkin, called over to them. “Boys, this is supposed to be quiet, independent study time.” Across the room, Alex Ryan snorted. Alex loved it when anybody else got yelled at.

Ethan read for a few more minutes. When he looked up from his book, he saw Lizzie, at the next table, watching him. Would she be jealous when she saw he was reading a longer book than hers? No, Lizzie didn’t seem competitive in that way.

The bell rang. Ethan was stuffing A Tale of Two Cities into his backpack when he heard Lizzie’s voice beside him.

“You’re reading Dickens?”

Ethan nodded warily.

“I love Dickens. Have you read Great Expectations? Or Oliver Twist? Oliver Twist is my favorite. I’ve read it twice. I cried both times when Bill Sikes murdered Nancy, even though she loved him so much. I can’t believe someone else in our class is reading Dickens.”

To his dismay, Ethan found himself walking down the hall to English with Lizzie by his side, still talking, talking, talking.

“I didn’t know you were such a big reader, Ethan,” Lizzie said. “I guess because your book-report books are always so short. But length isn’t what matters in a book. I love a lot of short books, too. Or look at poetry. A poem can be any length. There are millions of wonderful poems that are just a few lines long. Like Emily Dickinson’s poems. She can say more in two lines than most people can say in a hundred pages. What part are you up to in A Tale of Two Cities?”

They had reached the English room.

Standing Up to Mr. O.

Standing Up to Mr. O. Lucy Lopez

Lucy Lopez Dinah Forever

Dinah Forever Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star

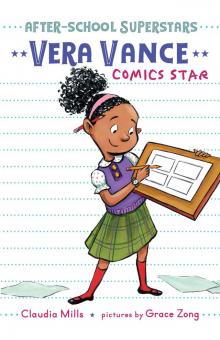

Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star Vera Vance: Comics Star

Vera Vance: Comics Star Izzy Barr, Running Star

Izzy Barr, Running Star You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman

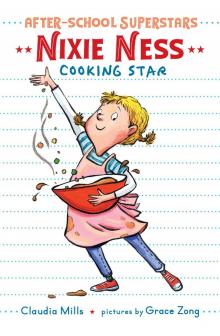

You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman Nixie Ness

Nixie Ness The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish

The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish Basketball Disasters

Basketball Disasters Being Teddy Roosevelt

Being Teddy Roosevelt Losers, Inc.

Losers, Inc. The Trouble with Friends

The Trouble with Friends Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ

Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants

The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants Annika Riz, Math Whiz

Annika Riz, Math Whiz Fourth-Grade Disasters

Fourth-Grade Disasters Pet Disasters

Pet Disasters The Trouble with Ants

The Trouble with Ants Write This Down

Write This Down Alex Ryan, Stop That!

Alex Ryan, Stop That! Kelsey Green, Reading Queen

Kelsey Green, Reading Queen How Oliver Olson Changed the World

How Oliver Olson Changed the World Lizzie At Last

Lizzie At Last Zero Tolerance

Zero Tolerance The Nora Notebooks, Book 2

The Nora Notebooks, Book 2 Cody Harmon, King of Pets

Cody Harmon, King of Pets Fractions = Trouble!

Fractions = Trouble! Makeovers by Marcia

Makeovers by Marcia One Square Inch

One Square Inch