- Home

- Claudia Mills

Fractions = Trouble! Page 3

Fractions = Trouble! Read online

Page 3

Wilson shrugged. Mrs. Tucker was helping him. Now he knew that the nice numerator was on top and the dumb denominator was on the bottom. And the big tent was 1/3 of the tents, while Snappy was ½ of Kipper’s beanbag animals. And ½ was actually bigger than 1/3, even though 2 was a smaller number than 3. But he didn’t want to say any of this to his mom. What if she made him go see Mrs. Tucker three times a week?

That afternoon Kipper and his mom made sleeping bags for Peck-Peck and Snappy out of squares of felt. They folded the squares in half (fractions!) and then sewed up two of the open sides. Peck-Peck and Snappy got new pillows, too, also made of folded felt, stuffed with cotton balls. To cut out the pillows, Kipper’s mom folded each square of felt in fourths (more fractions).

“You don’t take pillows on a camping trip,” their dad scoffed. “On a camping trip you’re supposed to rough it.”

Kipper ignored this remark.

Wilson had to admit that Peck-Peck and Snappy looked cute tucked into their matching sleeping bags with their little heads resting on their matching pillows. He almost made a sleeping bag himself for Pip, but she already had a cozy hamster “cave” just her size for sleeping.

At bedtime Kipper carried the two tiny sleeping bags outside and placed them tenderly in the tents, even though the wind was dying down. So 2/3 of the tents were now occupied.

“I want to sleep in a tent,” Kipper begged one last time.

His mother refused to give in.

“You belong in your bed,” she repeated. “And you belong in it now.”

Wilson had hoped that Josh would call and tell him what had happened with the pickle in the microwave, but he hadn’t. Maybe Josh was still mad that Wilson had done his “stuff” instead, and hadn’t even told him what the “stuff” was.

Finally, just before his bedtime, he called Josh. He had to call him, anyway. It was Josh’s weekend for Squiggles, and Wilson needed to ask Josh if he could borrow Squiggles on Sunday to work on the science fair.

“So?” Wilson asked, as soon as Josh picked up the phone. “What happened with the pickle? Did it explode this time?”

“Nah. This pickle got all wrinkled and weird-looking, and kind of brown and bumpy, but it didn’t blow up.”

“So pickles don’t explode.”

“Pickles don’t explode in an oven, or in a microwave. Next I’m going to try boiling one.”

Wilson waited to see if Josh would invite him to watch the third—and final?—attempt at a pickle explosion.

There was an awkward silence.

“What about you?” Josh asked. “Did you have fun doing your stuff this morning?”

“Not really,” Wilson said. “Oh, can I borrow Squiggles for a while tomorrow? I’ve decided I’m going to make my science fair project about seeing which color hamsters like best, and it would be better to do it with two hamsters instead of just one.”

“Sure,” Josh said. He didn’t offer to come over to help with the testing.

Then, “Well, see ya,” Josh said.

“See ya,” Wilson replied.

7

It didn’t turn out to be very windy that night, after all. All three tents were fine——when Kipper went out in the morning to wake up Peck-Peck and Snappy and bring them indoors for breakfast.

Josh’s dad dropped off Squiggles’s cage, with Squiggles inside it, at Wilson’s house mid-morning. Wilson had wondered if Pip and Squiggles would be happy to see each other, since they were sister and brother. When he placed them both on his bed, Pip just sat there blinking, but Squiggles darted down the covers and across the room, as if to get as far away from his sister as possible. Wilson liked Kipper more than that.

“I’m going to try to find out which color hamsters like best,” Wilson told Kipper, who had come into his room to help with the experiment.

“My favorite color is blue,” Kipper said. “Snappy’s favorite color is green. Peck-Peck’s favorite color is black.”

“I have a red bowl, a green bowl, a blue bowl, and a yellow bowl,” Wilson continued. “I’m going to put the same amount of food in each bowl and see which color they pick.”

“You don’t have a black bowl,” Kipper said.

“So?”

“So what if their favorite color is black, like Peck-Peck’s?”

Wilson took a deep breath. “I can’t try every single color in the whole world. Besides, we don’t have a black bowl. The set Mom bought just has these four colors.”

“What if each hamster has a different favorite color?” Kipper asked. “People don’t all have the same favorite color.”

Wilson did his best to remain patient. “That’s what we’re going to find out, Kipper.”

What Wilson found out, however, was that hamsters didn’t seem to have a favorite color at all. Sometimes Squiggles ran to the blue bowl, sometimes to the red one, sometimes to the green or yellow one. The same was true of Pip. Wilson wrote it all down in his science notebook, but he could tell he was getting nowhere. It had been, as far as Wilson could tell, a completely wasted hour.

“My teacher said hamsters are colorblind,” Kipper suddenly said. “She says hamsters can’t see color.”

Wilson stared at Kipper in disbelief. Now was the time that Kipper shared this tidbit of information?

“Why didn’t you say something sooner?” Wilson shouted.

Kipper pushed out his lower lip. “I just remembered. I can’t remember everything, Wilson!”

Without a word, Wilson put Squiggles in his cage and Pip in her cage. He walked out of his room and slammed the door.

Wilson didn’t like Kipper any better than Squiggles liked Pip, after all.

At school on Monday morning, Josh came up behind Wilson as Wilson carried Squiggles’s cage to its corner; Squiggles had spent the night with Wilson.

“How did Squiggles do?” Josh asked.

“Terrible. I tried to find out his favorite color, but guess what? Hamsters are colorblind.”

Josh laughed. “I boiled a pickle for a whole hour and it didn’t explode.”

Wilson laughed, too, glad Josh was being friendly again.

“Are there any other ways you can try to make a pickle explode?” Wilson asked. “You’ve already tried the oven, and the microwave, and boiling it.”

Josh’s face brightened. “Dynamite?” Then his face fell. “My parents won’t let me try dynamite.”

Wilson was relieved that there was at least one thing Josh’s parents wouldn’t let him do.

Laura, who had been standing nearby, joined the boys and clucked a friendly good morning to Squiggles in his cage. “I have an idea,” Laura said.

Both boys turned toward her hopefully. Laura always had great ideas.

“I got my science fair experiment out of a book that has hundreds of science fair projects. The project it had for hamsters was testing how far hamsters can smell.”

Wilson liked the idea already. “How do you do that?”

“You have to wait until they’re pretty hungry. Then you try putting their food at different distances until they pick up the smell and run over to get it.”

It sounded like a brilliant idea to Wilson.

“Becca is supposed to take Squiggles home this weekend, but I bet she’d let you have her turn,” Laura said.

Wilson shot her a grateful grin.

“Did the book have any science fair experiments you can do with pickles?” Josh asked.

Laura shook her head.

“I didn’t think so,” Josh said.

Wilson went to see Mrs. Tucker on Wednesday after school and again on Saturday morning. On Saturday, he drew a group of eight hamsters. First he colored three of the hamsters brown: 3/8. Then he colored two more brown: . That made five brown hamsters total, out of the group of eight: 3/8 + = 5/8!

When he filled pie-shaped circles with hamsters, two hamsters in a circle of eight took up the same amount of space as one hamster in a circle of four. So was equal to ¼!

Wilson drew hamsters u

ntil his hamster-drawing hand was about to fall off. His drawings covered Mrs. Tucker’s table.

“Thank you for letting me keep these,” Mrs. Tucker said. “I can use your drawings to help other children learn about fractions. I’m going to tell Mrs. Porter about them, too. I know she’s always looking for new ways to get her students interested in math, and this would be perfect, especially since all of you love little Squiggles so much.”

Wilson didn’t tell Mrs. Tucker that he was glad she was keeping his drawings so that no one would see him carrying them home and know that he was going to a math tutor.

Instead he told Mrs. Tucker about his progress on the science fair. “I’m going to do my smelling experiments this afternoon. I had to wait until Pip and Squiggles were hungry.”

“Call me when you get your results!” Mrs. Tucker said. “How is your brother’s tent project coming along?”

“He has the tents set up in the yard, but it hasn’t been windy enough yet to really test them.”

“Well, here in Colorado you won’t have to wait long for wind.”

It was true. There had been some mornings last month when it had been so windy that Wilson took Kipper’s hand on their way to school so his little brother wouldn’t blow away.

“Good luck this afternoon!” Mrs. Tucker said.

Neither hamster could smell the food bowl at five feet or at four feet, but they both could smell it at three feet. Wilson had proved something! He had proved an actual scientific fact! Maybe he’d even use fractions somehow on his science fair display board.

He called Mrs. Tucker and told her his results. He called Josh and told him. He’d tell Laura on Monday at school.

Wilson and Kipper left for school early Monday morning, carrying Squiggles’s cage, so Wilson could get him settled in his corner before the bell. The classroom was empty when Wilson arrived; Mrs. Porter must have been down the hall in the teachers’ lounge.

Once Squiggles had everything he needed—food, water, a farewell hug—Wilson turned around and saw the bulletin board.

He couldn’t believe it.

There, on the board, were four large, familiar-looking pictures of hamsters.

Wilson’s pictures.

Wilson’s pictures made with the math tutor.

Wilson’s pictures made with the math tutor for all the world to see.

8

Wilson snatched his pictures from the bulletin board, not caring as thumbtacks scattered across the floor. He ripped them in half, and in half again, and again. Then he took the torn scraps of paper and buried them in the bottom of the classroom recycling bin.

Mrs. Porter bustled into the room.

“Wilson, did you see that I put your wonderful drawings—” She broke off mid-sentence, staring at the bare bulletin board. “Why did you take them down?”

“I made them with the math tutor. Everyone will know I made them with Mrs. Tucker.”

“Oh, Wilson.” Mrs. Porter put an arm around his shoulders. “I wasn’t going to tell the class that you made your pictures with Mrs. Tucker. I was just going to say, ‘Look at what a creative way Wilson found to show us how to do fractions.’ Besides, there are lots of kids who get extra help.”

Wilson knew how Kipper felt when Kipper pushed out his lower lip and it started to tremble. “No one else goes to a math tutor.”

“How do you know that?”

Wilson just did.

The bell rang. Hordes of third graders came racing into the room.

“I’m sorry,” Mrs. Porter said softly. “I should have asked first.”

Wilson turned away so she wouldn’t see the Kipperish tears in his eyes.

A moment later, Josh gave him a hard, but friendly, whack on the back. “I wrote a poem last night about pickles. To put up on my science fair board. Do you want to hear it?”

Forcing a smile, Wilson nodded.

From a crumpled piece of paper, Josh read,

“Pickles boil and pickles burn.

But about pickles I have learned,

Unlike a frog, unlike a toad,

A pickle simply won’t explode.”

This time Wilson’s grin was real. “That’s good!” He couldn’t resist asking, “Do frogs and toads explode?” He also saw, looking over at Josh’s paper, that Josh was still spelling pickle as pickel. And he spelled toad as tode.

Josh shrugged. “I needed something to make it rhyme.”

During math time, Mrs. Porter gave the class a practice test and let them grade it themselves. Wilson got eight out of ten problems right: , which he now knew was the same as 4/5. That was definitely passing. If only he could do that well on the real test on Friday, then he could stop going to see Mrs. Tucker, and he could spend his Wednesday afternoons and Saturday mornings the way everyone else in the universe did.

The memory of his hamster drawings on the bulletin board made his cheeks burn, but at least he had gotten to the room in time to rip them down before anyone else had seen them. He noticed that Mrs. Porter had quickly covered the empty bulletin board with some perfect spelling tests. It was little comfort that one of them was his.

Out on the playground at lunch, Wilson saw Kipper playing tag with his little kindergarten friends. Kipper came running up to say hello as Wilson and Josh were hanging from the monkey bars in their favorite upside-down way.

Josh swung himself right-side up to return Kipper’s greeting. “What’s up, Kipper, my man?”

“It’s going to be windy tonight!” Kipper informed him.

Josh looked puzzled. “Are you afraid your house will blow down?”

“For the science fair! I have to see which tent does best in the wind. Remember?”

“Sure,” Josh said, but Wilson didn’t think he did.

“This time Peck-Peck is going to sleep in the little, low tent. Snappy is still going to sleep in the big, tall one.” Kipper held both Peck-Peck and Snappy up for Josh to see and made them do a little dance. “I don’t have anyone sleeping in the middle-sized tent.”

“How about a pickle?” Josh suggested. “I have a pickle that likes adventures.”

“You can’t put a pickle in a tent!” Kipper giggled.

“Why not? You haven’t met my pickle yet.”

Kipper giggled again. “When can I meet your pickle?”

“I’ll bring him over for a playdate. Yeah, we’ll have a playdate: you and me and Wilson and my pickle.”

Wilson was getting irritated. He had no intention of having a playdate with his little brother and Josh’s pickle. First Kipper had half of Wilson’s hamster; now Kipper was taking half of Wilson’s best friend. One half plus one half added up to the equivalent of one whole big thing that Kipper was taking away from Wilson.

“And Snappy and Peck-Peck can play, too,” Kipper added.

“Of course Snappy and Peck-Peck.”

“When can you come?” Kipper asked, as if he was going to start counting the hours.

“How about Wednesday? Right after school on Wednesday?”

“No,” Kipper said. “It can’t be Wednesday afternoon.”

“Why not?”

Before Wilson could hiss a warning to Kipper, it was too late.

“Because that’s when Wilson goes to the math tutor.”

“Kipper!” Wilson shouted.

Wilson didn’t stick around to see if Kipper was going to start crying, as usual. He shot one quick look at Josh. Josh was staring at his feet. Wilson could tell that Josh was embarrassed. Embarrassed to be Wilson’s friend.

Wilson turned around and walked across the blacktop to where some other kids were shooting hoops. He didn’t look back.

9

As soon as the boys got home from school, Wilson told his mother what Kipper had said to Josh on the playground. For once, Wilson’s mother wasn’t mad at him, but was mad at Kipper.

His mother’s face looked very serious as she sat Kipper down and said, “Kipper, Wilson can be the one to tell his friends about his math tuto

r, if he wants to.”

“But Josh asked.” Kipper’s face twisted into its most pathetic expression. “He wanted to come over on Wednesday afternoon, and I said Wednesday afternoon wasn’t good, and he asked why, and so I told him.”

“Having a tutor is private,” their mother explained.

Wilson couldn’t agree with her more. But he also knew that if having a math tutor was as wonderful as his parents claimed, it wouldn’t be private. His mother was practically admitting that having a math tutor was embarrassing.

Which it was. So embarrassing that Wilson’s own best friend couldn’t look him in the face once he found out.

“I’m sorry, Wilson,” Kipper sniffed in his most pathetic voice. “Peck-Peck and Snappy are sorry, too.”

What could Wilson say? “That’s okay.”

Wilson’s mother gave him a reassuring smile. Snappy and Peck-Peck tried to kiss him.

Wilson pushed them away.

Alone in his room, he lay on his bed for a long time, holding Pip and petting her small, soft head. Pip didn’t care that Wilson went to a math tutor.

Why couldn’t everybody else in the world be more like Pip?

That evening the wind rattled the windows and roared down the chimney as Kipper headed out to the backyard with Peck-Peck and Snappy to put them into their sleeping bags. Wilson was glad that Pip wasn’t sleeping in the empty third tent.

“Go with Kipper, Wilson,” his mother said. “It’s so windy out there.”

As if Wilson could do anything to make the wind stop its howling and shrieking.

First the two boys crawled into Peck-Peck’s low tent, and Kipper slipped Peck-Peck into his sleeping bag. He shone the beam of his flashlight onto Peck-Peck’s beak.

“Good night, Peck-Peck!”

Then the two boys unzipped the flap to Snappy’s tall tent. Kipper gave Snappy a good-night kiss before tucking him into his sleeping bag.

“Snappy’s afraid,” Kipper said. “Snappy doesn’t like the wind.”

Standing Up to Mr. O.

Standing Up to Mr. O. Lucy Lopez

Lucy Lopez Dinah Forever

Dinah Forever Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star

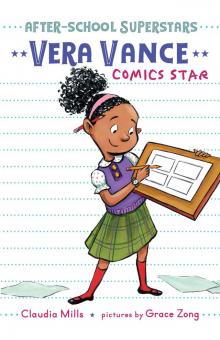

Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star Vera Vance: Comics Star

Vera Vance: Comics Star Izzy Barr, Running Star

Izzy Barr, Running Star You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman

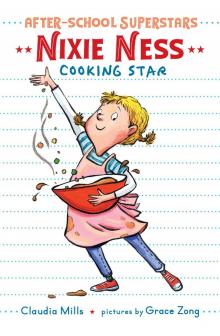

You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman Nixie Ness

Nixie Ness The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish

The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish Basketball Disasters

Basketball Disasters Being Teddy Roosevelt

Being Teddy Roosevelt Losers, Inc.

Losers, Inc. The Trouble with Friends

The Trouble with Friends Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ

Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants

The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants Annika Riz, Math Whiz

Annika Riz, Math Whiz Fourth-Grade Disasters

Fourth-Grade Disasters Pet Disasters

Pet Disasters The Trouble with Ants

The Trouble with Ants Write This Down

Write This Down Alex Ryan, Stop That!

Alex Ryan, Stop That! Kelsey Green, Reading Queen

Kelsey Green, Reading Queen How Oliver Olson Changed the World

How Oliver Olson Changed the World Lizzie At Last

Lizzie At Last Zero Tolerance

Zero Tolerance The Nora Notebooks, Book 2

The Nora Notebooks, Book 2 Cody Harmon, King of Pets

Cody Harmon, King of Pets Fractions = Trouble!

Fractions = Trouble! Makeovers by Marcia

Makeovers by Marcia One Square Inch

One Square Inch