- Home

- Claudia Mills

You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman Page 2

You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman Read online

Page 2

Julius looked down at Edison, still pulling at the door with all his might. Maybe his shorts did seem a little bulgy.

But the kid was three! He was a toddler, not a baby! Toddlers didn’t wear diapers anymore—did they?

No. Julius’s mother wouldn’t have done this to him. She wouldn’t have signed him up for a job where he would have to change diapers. He had never changed a diaper. He was never going to change a diaper. He didn’t know how to change a diaper. Diapers had … stuff in them. Stuff Julius didn’t even want to think about, let alone look at, let alone wipe.

“Come on, buddy,” Julius said. “This is getting boring. Let’s go do—” What? What did three-year-olds like to do? Besides have tantrums.

“I have an idea!” Julius said in an excited voice, as if he had reached into his pocket and found two free tickets to Disney World. “Why don’t you show me your room? I bet you have a cool room!” Ten minutes into the job, Julius was already starting to sound like somebody’s mother.

“No!” Edison said. But at least he let go of the doorknob. Julius grabbed the spare house key from the hook next to the door and quickly locked the deadbolt.

“Why don’t you show me your toys?”

“No!”

“Why don’t you show me your backyard?”

“No!”

Julius had an inspiration. “Why don’t you show me nothing?”

“No!”

“You don’t want to show me nothing? Okay, don’t show me nothing. Show me something. What do you want to show me?”

Edison had to think that one over. “Nothing,” he finally said, but Julius could tell Edison knew he had lost the first round.

“Ooh, I like your nothing!” Julius said. “Wow, Edison, that nothing is so cool!”

Edison giggled. Julius felt a small stir of satisfaction. So far, on the first day of summer, he had accomplished one thing. He hadn’t been able to say his name in French, but he had made Edison Blue laugh.

Edison was still in a good mood when he finally led Julius upstairs to his room. “Edison’s bed!” he shouted, leaping into the middle of a smaller-than-regular-size bed covered with a Winnie-the-Pooh bedspread.

He ran to the bureau. “Edison’s clothes!”

He ran to what was unmistakably a changing table. A diaper-changing table.

“Edison’s diapers!” The word caused him to burst into gales of laughter. Sure enough, there was a stack of disposable diapers in one of the bins beneath the changing table.

Julius’s blood ran cold.

There was no way that he, Julius Zimmerman, was going to change anybody’s diaper. That was final. Edison was going to have to wait until four o’clock on weekday afternoons to put anything in his diapers. If he did pee or poop before then, Julius was going to pretend that it had happened as Mrs. Blue was walking in the door. Three hours wasn’t that long. A kid could wait three little hours to have his diaper changed. Pioneer kids crossing the prairie in covered wagons had probably waited a lot longer than that.

Still, Julius wanted to get as far away from the changing table as possible. “Hey, buddy, show me Edison’s yard.”

He managed to get sunblock smeared on Edison’s chubby arms and legs. His face was harder. Or rather, his face was impossible. On little kids’ faces, everything was so close together that their cheeks and noses were right next to their eyes. Sunblock in your eyes could really sting. And the harder someone pulled away from you, the harder it was even to dab on sunblock, let alone rub it in. Julius got one little dot of sunblock on Edison’s left cheek before he gave up, hoping that you couldn’t get skin cancer in an afternoon.

Finally, they were ready to go outside. But as soon as they reached the large, square sandbox that stood next to the redwood play set, Edison turned difficult again. Instead of digging sand, he began throwing it. Julius could tell that he wasn’t throwing sand because he wanted to throw sand; he was throwing sand to see if Julius would stop him.

Julius said his line: “Hey, buddy, no throwing sand.”

Edison threw another handful of sand, a bigger handful this time.

Julius had tried being his mother; now he’d try being his father. He put on a sterner voice: “I said, no throwing sand.”

Edison threw his sand toward Julius.

Maybe with Edison you had to explain the reason for a rule. “Look, buddy, if you throw sand, it can get in somebody’s eye. In Edison’s eye. Edison no like sand in eye. Edison have to go to doctor. Doctor dig sand out of Edison’s eye. Ooh, that hurts Edison’s eye.”

Edison held his next handful of sand. Was he considering this line of argument, or wondering if his babysitter had suddenly lost the power to speak coherent English? Then he threw it.

Julius was getting angry now. He knew he wasn’t allowed to spank Edison, but he could give him a time-out. Mrs. Blue had discussed “guidelines for discipline” with him at the interview. She had told him he could place Edison in a time-out chair for a couple of minutes. She had also told him that the only problem with this was that Edison wouldn’t stay in a time-out chair for even a couple of seconds.

“That does it, buddy! You’re in time-out!”

Julius swooped down and gathered up a kicking, screaming Edison and set him down on the picnic bench.

“No!” Edison ran back to the sandbox.

Again, Julius carried him to the picnic bench.

Edison ran back to the sandbox.

Was Julius supposed to hold him in the time-out chair? He could, if he had to.

He carried Edison to the picnic bench once more. This time he held Edison, squirming and struggling, in place. Julius might be a spindly version of a twelve-year-old, but compared to a three-year-old’s, his physique was magnificent. He had Edison this time.

Until Edison bit him. On the hand. Hard.

“Owwww! You little—”

Edison burst free and ran back to the sandbox, to the exact same spot where he had been standing before Julius first carried him away.

Julius heard merry laughter. He looked up. Watching them from over the neighbors’ fence was a girl. Apparently she had been watching the whole time.

3

If babysitting for Edison Blue was bad, worse was babysitting for Edison Blue in front of an audience.

“I suppose you could do better,” Julius said defensively.

“I wouldn’t even try,” the girl said.

Julius remembered Mrs. Blue’s remark to his mother about how Edison might do better with a male babysitter. He had a sneaking suspicion that this girl with the mocking eyes had been the female babysitter who hadn’t worked out. It was only reasonable that the Blues would have started with their next-door neighbor before turning to him.

“I bet you did,” he said. “I bet the only reason I’m here making a fool of myself is that you already tried and failed.”

“You lose. I don’t sign up to do things I’m going to fail at.”

With the fence between them, Julius could see only her head and shoulders. She was around his height, and even though she looked sixteen, somehow Julius could tell that she only looked sixteen; he would guess that she was actually close to his own age. She was undeniably pretty, with straight dark hair that fell past her shoulders and large dark eyes. She certainly didn’t look like someone who’d ever failed at anything.

Julius turned to check on Edison, who was still standing in the sandbox, silently watching them and not throwing sand. Julius realized that he had discovered something important: three-year-olds can be distracted.

He turned back to the girl again, wondering if he could steer the discussion in a friendlier direction. He wasn’t used to chatting casually with someone who was so pretty.

“So do you babysit for any other kids?” Most of the girls Julius knew loved little kids and had counted the months until they were old enough to babysit.

The girl gave him a scornful look. “Life is too short.”

She had a point there. Fo

rget life: summer was too short to spend babysitting, much less learning French, and yet somehow Julius was doing both.

Julius tried to think of something else to ask her. He wanted to prolong the conversation that was distracting Edison so effectively. “What do you do instead?”

“I dance. I sing. I act.”

It was easy to imagine her on the stage. She was definitely a dramatic figure, with her dark coloring and her expressive face.

“Do you want to be an actress?” Julius asked.

“I am an actress. I played Juliet last year in the Waverly School’s production of Romeo and Juliet.” The Waverly School was a fancy private school. It figured. “And I’m auditioning for the Summertime Players production of Oklahoma! in a couple of weeks.”

She studied Julius with what seemed to be genuine interest. “What about you? What do you do when you’re not babysitting l’enfant terrible?”

Julius didn’t understand the last part of the question, though something about it sounded vaguely familiar. Lon-fon terrr-eebl?

“It’s French for ‘the terrible child.’”

“Actually, I’ve been studying French.” Maybe that would impress her.

“How long?” she demanded skeptically, as if anyone who had studied French for more than one day would know the French words for “terrible child.”

“One day,” Julius admitted. So much for impressing her.

“Comment vous appelez-vous?” she asked.

Wait a minute. He knew what that meant. Julius couldn’t believe that less than two hours out of his first French class he was being asked a question in French that he could not only understand but maybe even answer. He gave it a try: “Je m’appelle Julius Zimmerman.”

He must have said it right, because the girl smiled. She had an incredible smile that seemed to say the person she was smiling at was her favorite person in the whole entire world. “Je m’appelle Octavia Aldridge.”

Julius glanced back to check on Edison again. A stinging handful of sand struck him on his bare arm.

“I think this is my cue for an exit,” Octavia said. “Au revoir, Julius. I wish you luck. Lots of luck.”

Julius didn’t know if he was relieved or sorry to see her go. He glanced at his watch. Two more hours. Two more hours to be the target of Edison’s sand-throwing.

Distraction, he remembered. Distraction was the key.

Julius suggested a nap. Edison didn’t want to take a nap.

Julius suggested a story. Edison didn’t want to hear a story.

Julius suggested a nap again. Kids small enough to be wearing diapers should still be taking afternoon naps. But Edison hadn’t changed his anti-nap stance since the previous suggestion.

Then Julius suggested a snack. He himself was ravenous, as if he’d been working all day at hard labor on a chain gang. This time, Edison followed Julius into the kitchen.

The snack worked out pretty well, although Edison spilled his juice all over his I Virginia Beach shirt and had a tantrum when Julius wouldn’t let him eat a crumbled cookie that had fallen onto the Blues’ none-too-clean kitchen floor. In the end, Julius let him eat it. Kids had probably eaten worse things than that and survived.

It was only two-fifteen. Suddenly Julius remembered: TV Edison’s mother had told him at the job interview that she didn’t want him and Edison to spend their time together staring at the TV but Julius decided she couldn’t possibly have meant it. Besides, they weren’t spending their whole time together watching TV. Edison had spent almost half of it having tantrums.

Anyway, he’d turn it off at three fifty-five and hope that Edison had the sense not to tell.

Julius clicked around the channels until he found the Flintstones. He had written in his goals journal that he would watch two hours a day of TV maximum, educational programs only, but surely cartoons with Edison didn’t count toward his own limit.

Peace descended on the Blue household. There were two couches in the family room. Julius sprawled on one. Edison sprawled on the other. The Flintstones were followed by Bugs Bunny. Bugs Bunny was followed by Porky Pig. The afternoon wasn’t turning out so badly, after all.

At three-fifty, to be on the safe side, Julius announced in his now-perfected fake-cheerful voice, “All right, buddy! We have to let the TV rest now!”

No sooner had he clicked the power button than a loud wail arose from Edison.

“More TV!”

“No, no, buddy. The TV’s tired. Poor TV! It needs to go for a nice little nap.”

“TVs don’t take naps!”

All right, so the kid wasn’t dumb. “Well, it doesn’t need to take a nap, exactly, but it can break if we don’t turn it off for a while and let the circuits cool down.”

Edison considered this explanation. He seemed to know that it was better than the first one Julius had given, but it still wasn’t good enough.

“More TV!”

Julius was getting desperate. Desperate enough to try the truth. “Look, your mom said we weren’t supposed to watch TV She’s going to be here any minute, and if she finds us watching TV, we’re going to be in big trouble. Both of us. You and me.”

The mention of Edison’s mother turned out to be a mistake.

“I want my mommy!” The cry was so loud that Octavia could probably hear it a house away.

“She’s coming! Any minute now!” At least Julius hoped she was. If she was late, he didn’t know what he’d do.

But she wasn’t late. Mrs. Blue appeared promptly at four, just as Edison had stopped shrieking, “I want my mommy!” and had gone back to shrieking, “More TV!”

Mrs. Blue flew to Edison and caught him up in a big hug. It wasn’t a fake hug, either, as far as Julius could tell. Hard as it might be to believe, Edison’s mother actually loved him.

Then, when Edison was finally quiet, Mrs. Blue turned to Julius. “How did it go?”

“Pretty well,” Julius said, relieved that she hadn’t asked what Edison had meant by crying “More TV!” And it had gone pretty well, all things considered. Edison hadn’t pooped in his diaper, though Julius could smell that he had deposited a generous quantity of pee-pee in it. There had been no visit to the emergency room, no frantic calls to 911. The house was still standing.

“Julius, what was Edison saying about more TV?”

Julius kept his tone professional and polite. “I had some trouble getting him calmed down after his snack, so we watched a little bit toward the end.”

“Just a little bit, though.” Luckily she didn’t pause for confirmation. “I guess that’s all right. I know the afternoons can get a bit … long sometimes. Speaking of which: angel, it’s time for us to say goodbye to Julius.”

“Bye, Edison!” Julius said. If there was ever a contest for the two most beautiful words in the English language, he had his entry ready.

“No! Julius stay!”

To Julius’s great surprise, Edison sprang across the room and attached himself to Julius’s leg.

“Hey, buddy, I’ll be back! I promise!”

For the next few minutes, Julius’s leg was the scene of a tug of war. Edison tugged on Julius’s leg; Mrs. Blue tugged on Edison. Finally, fortunately for Julius, Mrs. Blue won.

Julius didn’t linger for another round of farewells. He bolted out the door to freedom. Though he had to admit that he had found Edison’s last tantrum oddly gratifying. Maybe you weren’t a total failure as a babysitter if the kid cried when it was time for you to leave.

As he unlocked his bike, he heard from the family room the unmistakable theme music of Looney Tunes. Afternoons with Edison could get long, all right.

* * *

Julius made a beeline for Ethan’s house. He and Ethan hung out and shot a few baskets until six o’clock. They were both lousy players, but liked playing, anyway. Then Julius headed home. His mom had a deadline looming on a writing project, and his dad was working late at his accounting office, so dinner was leftover Chinese carryout that Julius heated up f

or his mom and himself in the microwave.

“Okay, now tell me,” his mom said as she picked up her chopsticks. “How was your first day at your very first job?” She emphasized the word as if Julius were a little kid, Edison’s age, and she was trying to make him feel important. “Did you get off to a good start with Edison?”

Had he gotten off to a good start with Edison? His hand still hurt from where Edison had bit him, but he also still felt secretly pleased that Edison had cried when it was time for him to go. “I guess so,” he said.

“What kinds of things did you do with him?”

Julius thought over his possible answers: Let him bite me, let him throw sand at me, watched a bunch of dumb cartoons on TV.

“Just things,” he said.

His mother didn’t look satisfied, but she changed the subject.

“I took a little break this afternoon and went to the library,” she said. “I came home with more books than I can possibly read in two months, let alone two weeks, but I couldn’t resist. How about you? Have you picked out which book you want to read this week?”

She had to be joking. It was only Monday. He wasn’t going to start on his week’s reading goal on a Monday. Besides, how could he come home from a morning spent with Madame Cowper and an afternoon spent with Edison Blue and then spend his evening reading age-appropriate books and filling in pages in his Sixth-Grade Math Review Workbook? His mother couldn’t expect him to attempt the impossible. Fortunately, he had made this discovery in time to revise his week’s goals.

After dinner, Julius opened his green-covered journal and wrote:

Goals for the Week of June 9–15, Revised

1. Try not to make a fool of yourself in French class.

2. Get Edison Blue to stop throwing sand.

3. Limit Edison’s TV to one hour per afternoon—no sex or violence.

4. Try to keep Edison from pooping in his diaper.

Standing Up to Mr. O.

Standing Up to Mr. O. Lucy Lopez

Lucy Lopez Dinah Forever

Dinah Forever Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star

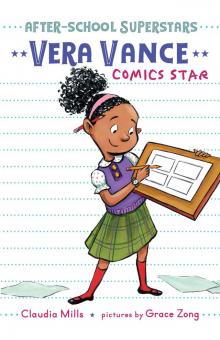

Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star Vera Vance: Comics Star

Vera Vance: Comics Star Izzy Barr, Running Star

Izzy Barr, Running Star You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman

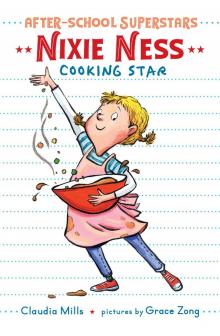

You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman Nixie Ness

Nixie Ness The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish

The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish Basketball Disasters

Basketball Disasters Being Teddy Roosevelt

Being Teddy Roosevelt Losers, Inc.

Losers, Inc. The Trouble with Friends

The Trouble with Friends Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ

Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants

The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants Annika Riz, Math Whiz

Annika Riz, Math Whiz Fourth-Grade Disasters

Fourth-Grade Disasters Pet Disasters

Pet Disasters The Trouble with Ants

The Trouble with Ants Write This Down

Write This Down Alex Ryan, Stop That!

Alex Ryan, Stop That! Kelsey Green, Reading Queen

Kelsey Green, Reading Queen How Oliver Olson Changed the World

How Oliver Olson Changed the World Lizzie At Last

Lizzie At Last Zero Tolerance

Zero Tolerance The Nora Notebooks, Book 2

The Nora Notebooks, Book 2 Cody Harmon, King of Pets

Cody Harmon, King of Pets Fractions = Trouble!

Fractions = Trouble! Makeovers by Marcia

Makeovers by Marcia One Square Inch

One Square Inch