- Home

- Claudia Mills

Being Teddy Roosevelt Page 2

Being Teddy Roosevelt Read online

Page 2

“My mother is going to help me. People helped Helen Keller, too, like her teacher, Annie Sullivan.”

“Where did you learn so much about Helen Keller?” Riley asked. “You haven’t even gotten your biography yet.”

Sophie shrugged. “Everybody knows some things.”

Riley felt as if he didn’t know anything.

Riley’s mother and Grant’s mother hadn’t returned yet. Sophie’s mother was typing away at the computer catalog across the room.

“Let’s play a trick on Sophie,” Grant whispered.

“Like what?”

Grant got down on all fours and crawled over to Sophie’s feet and started meowing. Riley set his book down to watch him.

“Very funny, Grant-the-cat.”

Grant tried again. “Oh, Sophie, look! There’s a snake crawling into the library. A long, slithery one.”

“A snake in the library,” Sophie said scornfully. “I suppose it just opened the door and came in all by itself?”

“Wait! There’s a spider! A big black hairy one. It’s coming right toward you!”

It was hard to tell what someone was thinking when you couldn’t see her eyes. But this time Sophie wasn’t so quick with her response.

“I’m not afraid of spiders,” she said uncertainly.

“There really is a spider!” Grant told her. “Honest! I wouldn’t lie about something like that. I’ve never seen such a big one!” He reached out a hand and brushed Sophie’s arm.

Sophie gave a muffled scream and tore off her blindfold. “Where is it? Where’s the spider?”

Grant burst out laughing. Sophie glared at him with pure rage.

“If you were really Helen Keller, you wouldn’t be able to take off your blindfold,” Grant said.

“Well, if you were really Mahatma Gandhi, you wouldn’t be playing stupid tricks on people.”

“Guess what? I’m not really Mahatma Gandhi. Lucky me.”

Sophie’s mother came bustling over. “I found three biographies. I know you’ll want the longest one. I’m glad you took off that blindfold, honey. It’s well and good to practice being Helen Keller, but a little bit of pretending goes a long way.”

“I’ve practiced being blind enough for one day.” Sophie swept off with her mother to the nonfiction stacks.

Riley wondered whether Teddy Roosevelt had ever played tricks on people. He didn’t know anything about Teddy Roosevelt, except that he was President and had a mustache and had his head carved on Mount Rushmore.

Back at home, Riley thought he might look at the first page of his biography, to see how hard it was going to be. But where was it?

“I can’t find my library book,” Riley confessed.

“Oh, Riley. It has to be here somewhere.”

Riley looked everywhere. He still couldn’t find it.

“I think I left it at the library.” He had a dim memory of laying it down on a table while Grant was meowing at Sophie.

“Oh, Riley,” his mother said again. “The library’s closed now. We’ll have to go back tomorrow and hope it’s still there. Do you see why I don’t want to rent a saxophone?” She sounded tired and discouraged.

Riley felt tired and discouraged, too. He bet Teddy Roosevelt didn’t forget everything. A person who forgot his own head if it weren’t fastened on wouldn’t get his head carved on Mount Rushmore.

4

During reading time on Fridays, Mrs. Harrow let her students sit anywhere they wanted: on the rug, in the beanbag chairs by the bookcases, even outside on days that were warm and sunny—anywhere but on the couch. Only the two special students who were the “couch potatoes” for the week were allowed to sit on the couch. The couch potato names were drawn from Mrs. Harrow’s big papiermâché potato.

This week Riley was a couch potato.

Unfortunately, Erika was a couch potato, too.

If only Riley and Grant could have been couch potatoes together. But so far this year, Mrs. Harrow’s potato had never picked best friends in the same week. Riley sometimes wondered if it was rigged.

Grant plopped down on the floor next to the couch, like a couch potato that had rolled onto the floor. A floor potato. The couch potatoes and the floor potato started reading.

Riley read slowly. There were a lot of hard words in his biography of Teddy Roosevelt, which he had brought home from the library yesterday. Words like asthma. When he was a little boy, Teddy Roosevelt had asthma. Asthma was a sickness that made it hard to breathe. When young Teddy had trouble breathing at night, his father would take him out for rides in his carriage.

Teddy Roosevelt was lucky to have a father, Riley thought.

And to be rich. The Roosevelts had piles and piles of money. If Teddy Roosevelt had wanted a saxophone, his father could have bought him one in a second.

But maybe, since Teddy had asthma, it would have been hard for him to blow into a saxophone.

Still, it was even harder blowing into a saxophone if you didn’t have a saxophone—and were never going to have one.

At the other end of the couch, Erika slammed her book shut. Uh-oh. Grant looked up from his. Riley saw that Grant was already on chapter three.

“How’s empire ruling?” Grant asked pleasantly.

A spot of red burned in each of Erika’s cheeks. “It’s Queen Elizabeth’s father. Guess what he did.”

Riley had no idea.

“He made her sit cross-legged in her underwear?” Grant suggested, even though Erika was clearly in no mood for jokes.

“Queen Elizabeth’s father,” Erika said, “cut off Queen Elizabeth’s mother’s head.”

That was bad, all right. Maybe fathers weren’t such a great thing—at least some of them.

“Why did he do that?” Grant asked.

Erika’s eyes glittered with rage. “He did it because he was mad that Elizabeth wasn’t a boy. He wanted a boy.”

“That’s awful,” Riley said, so Erika would know that he didn’t agree with Queen Elizabeth’s father at all.

“Maybe you should have kept Florence Nightingale,” Grant suggested.

Ignoring Grant, Erika opened her book again.

“I guess she doesn’t think she should have kept Florence Nightingale,” Grant said.

“Be quiet,” Erika snapped at him. “I want to find out what happens next.”

“How’s Gandhi?” Riley whispered to Grant.

“He’s wearing normal clothes so far,” Grant whispered back.

Riley returned to reading. Teddy’s father told him that he would have to cure himself from being weak and sickly. He was going to have to make his body. So Teddy started lifting weights and pulling himself up on rings and bars. He asked to take boxing lessons and learned how to box.

Riley’s thoughts wandered. What if he had a father who said, “Riley, you must make yourself into a saxophone player!” Then his father would buy him a brand-new saxophone, the way Mr. Roosevelt had built Teddy his own private gym. Just as Teddy Roosevelt had asked his father for boxing lessons, Riley would ask his father for sax lessons.

“Sure, son,” he imagined his father saying with a proud grin. Riley practiced the proud grin.

“What are you smiling about?” Grant asked him.

The question pulled Riley back to reality.

“Nothing.” He had no father, no sax, no lessons, no proud grin.

Riley wondered what Teddy Roosevelt would have done if he hadn’t had a rich father who could give him anything he wanted. Riley was only up to page 19, but he already knew that if Teddy hadn’t been given a gym, he would have built himself one. If he hadn’t had weights to lift, he would have lifted chairs, or rocks, or bales of hay.

Unfortunately, there was no substitute for a saxophone. Teddy could lift anything and build strong muscles. Riley couldn’t blow into just anything and make music.

But still. If Teddy Roosevelt had wanted a saxophone, he would have gotten himself a saxophone. Somehow.

Riley read another

few pages. Teddy Roosevelt’s father died! Riley felt sorry for Teddy Roosevelt even though he was just reading about him in a book. Teddy Roosevelt had been a real person, and everything in the book was true. Riley didn’t have a father, and now Teddy Roosevelt didn’t have a father, either. Riley and Teddy were the same.

Riley opened his language arts notebook—he had remembered to bring it to school that day!— and found a blank page halfway through.

Ways to Get a Saxophone, he wrote at the top of the page.

But he couldn’t think of a single thing to write next. Make one. He couldn’t make a saxophone. Find one. Like where? And if he found one, it would probably belong to someone else. “Finders keepers” didn’t apply to saxophones. Borrow one. From whom? Earn the money to get one.

That idea didn’t seem as dumb as all the rest.

It might even be, as Teddy Roosevelt would have said, a bully idea. According to Riley’s book, bully meant “great, terrific, wonderful.”

Earn the money to get one, Riley wrote on his page.

Of course, he didn’t know how much money he’d have to earn, or how a nine-year-old kid could possibly go about earning it. And even if he did, his mother had said he shouldn’t do instrumental music because he was having enough trouble getting his regular homework done.

Riley added to his list: Do better on my homework so my mom will let me have one.

“All right, class!” Mrs. Harrow called out. “Reading time is over. Go back to your desks and get out your math books.”

Riley got off the couch. Erika shut her book with a bang. She must still be mad at Queen Elizabeth’s father.

At least Riley had started a list. Step one was making a list of what to do.

But the harder part was step two: doing it.

5

On Saturday morning, Riley settled down on the couch to watch cartoons. He knew he should be reading his Teddy Roosevelt book, but he could learn about Teddy Roosevelt later.

Riley’s mother clicked off the TV.

“Mom!”

She waved the newspaper at him. “We’re going to yard sales.”

Riley groaned, but his mother ignored him. She loved yard sales the way Grant loved video games, the way Mrs. Harrow loved biography teas. She loved yard sales the way Riley loved saxophones.

Reluctantly, Riley shoved his feet into his sneakers.

“We can look for items for your Teddy Roosevelt costume,” his mother said. “What did Teddy Roosevelt wear?”

Riley checked the cover of his book. “A fringed jacket, and boots, and a hat, and a bandanna, and these weird glasses that sort of stick on your nose, and a mustache.”

“Well, we can look, at least.”

Riley imagined the ad in the newspaper:

HUGE YARD SALE!

Come buy glasses that stick on your nose!

Mustaches!

“Can Grant come, too?”

“I doubt Grant wants to spend his morning at yard sales.”

But when Riley called him, Grant did want to go. “Better yard sales than working on my report or trying to figure out how to play my trumpet.”

Grant’s parents had already bought him a brand-new trumpet for instrumental music. Sometimes Riley couldn’t help feeling jealous of Grant.

“Maybe we can find some great-looking loincloths,” Grant said.

Sometimes Riley didn’t feel jealous of Grant.

The first yard sale had lots of baby things: a crib, a stroller, piles of tiny clothes. It had adult clothes, too, but nothing Teddy Roosevelt or Mahatma Gandhi would have worn. No mustaches, no loincloths.

The next yard sale had a whole table full of used video games. Grant had them all. Riley didn’t have any of them. But he wasn’t going to spend his money on video games. Not if he could save it to buy himself a saxophone. He had five dollars and fifty cents crammed into his pocket right now.

The man at the third yard sale looked familiar. Riley was sure he was somebody’s dad from school. Then a woman came out of the house. It was Sophie’s mother.

“Let’s go,” Riley said. “There’s no good stuff here.”

“We haven’t even gotten out of the car yet!” Riley’s mom protested. “And look! There’s Sophie’s mom. You boys can chat with Sophie if you don’t see anything that interests you.”

Luckily, Sophie was nowhere to be seen. Maybe she was at the library, filling out her seven hundredth note card on Helen Keller.

Riley and Grant started looking at the sale tables. Sophie had an older brother, so there might be something worth buying, after all. Grant found a video game he didn’t have and almost fainted with joy. Riley found a red bandanna that cost a quarter. Now all he needed was the jacket, the boots, the hat, the glasses, and the mustache.

Then, next to a stack of old National Geographic magazines, Riley found something that made his heart race. It was a book of music. Saxophone music. Alto saxophone music for the beginner.

Riley stared at the book. Where there’s saxophone music, there must be a saxophone.

“Hi, Grant. Hi, Riley.” It was Sophie. Apparently her seven hundred index cards were filled out already.

Grant held up his video game. “Hey, Sophie, how come your brother turned out normal?”

Sophie didn’t react.

Grant tried again. “How come he turned out normal when you’re so strange?”

Sophie just smiled. Grant looked puzzled. Then Sophie pointed to her ears. “I have my earplugs in. I’m practicing being deaf today. So far it’s a lot easier than being blind. For one thing, I don’t have to listen to any dumb comments from boys.”

But how was Riley going to ask her about the saxophone if she couldn’t hear? Not that he had the nerve to ask.

Sophie’s mother came over to the table. “Are you boys finding anything?”

It was now or never. “Um.”

That was as far as Riley got. He pointed to the saxophone music.

“I think the price on that is marked. Yes, it’s twenty-five cents.”

Riley had a quarter. But what good was saxophone music without a saxophone?

“You don’t have … You aren’t selling …”

Grant drifted off to another table, and then Riley whispered, “A saxophone?”

Instantly Grant whirled around. “A saxophone? What do you want a saxophone for?”

Riley’s mother, browsing at the next table, gave him a worried look. “But, Riley, I thought we said …”

Sophie’s mother hesitated. “Jake isn’t playing his sax anymore. I’ll ask him if he wants to sell it.” She hurried inside.

“You want to do instrumental music?” Grant asked.

Riley nodded.

“What about your homework, Riley?” his mother asked gently. “We’ve already talked about this, remember?”

“If I can do saxophone, I’ll study harder. I’ll study three hours a day.” Well, two. “I’ll get all B’s.” Well, C’s. “I’ll do the best I can. I will. I promise.” That much was true.

Riley’s mom’s face softened. “Well, if it doesn’t cost too much, and if you truly promise to apply yourself to your schoolwork, I’ll let you do instrumental music.”

Sophie’s mother came back out of the house, carrying a saxophone case. She set it on the grass next to Riley. He wanted to reach down and touch it, but he didn’t.

“It’s practically brand-new,” Sophie’s mother said. “I could let you have it for …”

Five dollars! Five dollars and fifty cents!

“A hundred dollars, I guess.”

“I’m sorry,” Riley’s mother said. She sounded sorry, too, sorrier than Riley had heard her sound about anything for a long time. “That’s too much for us right now.”

Riley wasn’t going to cry, he wasn’t. Teddy Roosevelt wouldn’t cry. Teddy’s first wife died, and he came in last in his election for mayor of New York City, but he didn’t cry. He kept on trying.

“Do you still want the sax music?”

Sophie’s mother asked.

Riley almost shook his head.

Then slowly he pulled out his two quarters, one for the bandanna, one for the music book.

One bandanna didn’t make you Teddy Roosevelt.

One used music book didn’t make you a musician.

But at least it was a start.

6

“I need to go to the library again,” Riley told his mother the next Saturday.

“Oh, Riley, you didn’t lose that biography, did you?”

“No!” Riley said indignantly. He really was getting better. He had finished reading the whole entire biography of Teddy Roosevelt, and he had twenty index cards already. And he had found a great stick-on mustache at the downtown costume store for just seventy-nine cents.

That meant he had seventy-nine cents less in his saxophone fund. Maybe he could sell his mustache after the biography tea, if there was still enough sticky stuff left on the back.

“So why do you need to go to the library?” his mother asked.

“Mrs. Harrow wants us to look at three other sources for our report. Like encyclopedias. Or the Internet. I can take the bus if you don’t want to drive me.” The public bus ran every ten minutes between Riley’s house and downtown; kids under ten could ride for free.

His mother hesitated. She was curled up on the couch, reading the newspaper in her pajamas. “If Grant goes with you, I suppose you’ll be all right. Just pay attention to where your stop is. And check that you don’t leave anything on the bus.”

“Mom! I won’t leave anything. All I’m taking is my envelope of note cards.”

“It never hurts to check,” she said.

It was fun riding the bus with Grant, sitting in the backseat, arguing about who got to pull the cord when it was time to get off. When Riley pulled it at their stop, he felt grownup enough to be in middle school.

At the library, they saw lots of other kids from school: Harriet Tubman, Martin Luther King, Jr., Louisa May Alcott—and Helen Keller.

“You’re not done with your note cards yet?” Grant asked. “I don’t believe it.”

Standing Up to Mr. O.

Standing Up to Mr. O. Lucy Lopez

Lucy Lopez Dinah Forever

Dinah Forever Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star

Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star Vera Vance: Comics Star

Vera Vance: Comics Star Izzy Barr, Running Star

Izzy Barr, Running Star You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman

You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman Nixie Ness

Nixie Ness The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish

The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish Basketball Disasters

Basketball Disasters Being Teddy Roosevelt

Being Teddy Roosevelt Losers, Inc.

Losers, Inc. The Trouble with Friends

The Trouble with Friends Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ

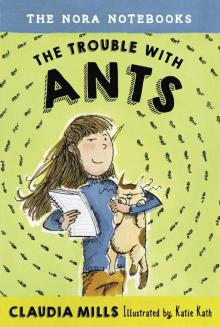

Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants

The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants Annika Riz, Math Whiz

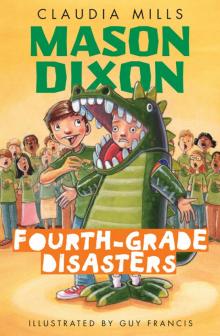

Annika Riz, Math Whiz Fourth-Grade Disasters

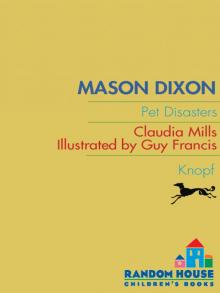

Fourth-Grade Disasters Pet Disasters

Pet Disasters The Trouble with Ants

The Trouble with Ants Write This Down

Write This Down Alex Ryan, Stop That!

Alex Ryan, Stop That! Kelsey Green, Reading Queen

Kelsey Green, Reading Queen How Oliver Olson Changed the World

How Oliver Olson Changed the World Lizzie At Last

Lizzie At Last Zero Tolerance

Zero Tolerance The Nora Notebooks, Book 2

The Nora Notebooks, Book 2 Cody Harmon, King of Pets

Cody Harmon, King of Pets Fractions = Trouble!

Fractions = Trouble! Makeovers by Marcia

Makeovers by Marcia One Square Inch

One Square Inch