- Home

- Claudia Mills

Zero Tolerance Page 14

Zero Tolerance Read online

Page 14

That she said exactly the same words Luke had said when he was contemplating his own expulsion made Luke laugh out loud.

“You think that’s funny, don’t you,” Ms. Lin said. She still didn’t sound angry. “Well, let me tell you, I’m glad to get your apology, but after today I’d prefer never to see another middle school student again as long as I live. Or another middle school principal.”

Ms. Lin didn’t look at Sierra and Luke as she spoke.

“I’ve spent eighteen years in a job I hated,” she went on, “and yesterday I took some of my ample savings—I call it my blood money—and I bought myself a ticket for a monthlong vacation trip to Nairobi.”

“Nairobi?” Sierra asked.

“The capital of Kenya. I guess Mr. Besser’s astonishing educational initiatives haven’t reached as far as teaching world geography. I’m leaving in two weeks.”

“I hope you have a good time,” Sierra said.

“Oh, I will. Believe me, I will.”

“I guess we should go now.”

“I guess you should.”

Sierra and Luke stood up.

“Your apartment is pretty,” Sierra said.

“Thank you,” Ms. Lin said. “Now go, both of you. Just go.”

Sierra and Luke put on their coats and their shoes and left.

38

Luke offered to walk home with Sierra.

“But you live in the opposite direction,” she protested.

“So?”

“Oh, Luke,” she said. “Right now I need to be by myself for a little while to sort things out, okay?”

And he didn’t get huffy or touchy. He just said, “Sure, I’m cool with that,” and gave her another hug.

Sierra started her long, cold walk. She knew that all she would have to do was call her mother on her cell phone and her mother would be there in five minutes, but she needed some time to think.

The hearing was tomorrow morning at ten.

Tomorrow her father was going to squish Mr. Besser like a bug, and Sierra was going to find out if the superintendent of schools was going to expel her or let her stay at Longwood Middle School.

So one way or another, this had been her last day ever of suspension. By Monday she’d be either reinstated or expelled. And she had spent her last day in suspension falling in love with Luke Bishop!

If she was expelled, she’d be starting either at Beautiful Mountain or at some other, more “academic” school chosen by her father. He hadn’t mentioned anything about what school he’d like her to attend once she was expelled from the public school district. Apparently he was so confident he’d prevail at the hearing that it wasn’t worth his time to consider any alternatives. Probably, if he had to, he’d pick Braxton Country Day School, the fancy private school north of town. Sierra would never fit in with the snobby rich kids there.

But even if she was reinstated at Longwood Middle School, it would never be the same. She’d never again be Sierra Shepard, fine student leader. She’d be Sierra Shepard, who was almost expelled for bringing a knife to school. Sierra Shepard, who didn’t get to go on the big choir trip. Sierra Shepard, who had already missed a week of work in every class and would never be able to catch up. Sierra Shepard, who hung around with Luke Bishop.

Sierra’s fate would be decided tomorrow morning.

Though her fate had really been decided the minute she opened her lunch bag at school on Wednesday, January 23. No, even before: when she had picked up the lunch bag that morning. And Mr. Besser: his fate had been decided when he had told that other principal that zero tolerance meant zero tolerance, with no exceptions ever. No, earlier, when he had drunk too much and gotten behind the wheel of a car on the evening of November 29. Ms. Lin’s fate had been decided when she stepped away from her desk on Monday, January 28, to go to the bathroom.

And Sierra’s parents: their fate had been decided when her father had laughed during her mother’s play. If that hadn’t happened, they wouldn’t have gotten married, and Sierra wouldn’t have been born, and she wouldn’t be twelve years old right now and ready to find out whether or not she was going to be expelled from Longwood Middle School.

Tomorrow at ten.

39

At eight-thirty the next morning Sierra awoke to find her bedroom filled with the dazzling brightness of sun after snow.

Still not fully awake, she checked her phone: five texts. She had turned it off the previous evening, unable to face any messages from anybody.

Celeste: Good luck today. I wish you were going with us.

Colin: I hope you win. You deserve to.

Lexi: Em told me about C and C. Are you okay?

Em: OMG, was that you walking with Luke B? Call me!

Luke: Suspension sucks without u. Miss u bad.

Sierra wasn’t going to text anybody back. But then she did text Luke: miss u 2.

In the kitchen, her father was seated at the breakfast table, handsome in his gray attorney suit, reading The New York Times. He looked up from the paper to give her a confident smile.

“In less than two hours, all this will be behind you, sweetheart.”

Then he seemed actually to see her, still in her pajamas. “You’re not dressed yet. Wear something preppy. The school uniform look. Do you have a plaid skirt? White blouse? Dark blazer?”

Her mother was wearing a dress—less long and flowy and Beautiful Mountain–ish than most of her other clothes. Maybe Sierra’s father had coached her, too, on what to wear to a daughter’s expulsion hearing.

“Breakfast first,” her mother said. “Eggs today, I think. How about a small omelet with spinach and cheese?”

“I’m not really—”

“Yes, you are,” her mother said. “You need to eat.”

Apparently it wasn’t a good idea to go to an expulsion hearing on an empty stomach.

“Where is the hearing?” Sierra asked.

“At the Board of Education complex,” her father replied. “That big new bunch of buildings they built after the last bond issue. Over on Twenty-ninth Street and Pine.”

“Who else will be there? Besides us, and Mr. Besser, and the superintendent?”

“Probably the attorney for the school district, because this has become such a high-profile case.” A flicker of pleasure passed over his face: he knew who was responsible for its having become “such a high-profile case.”

“And the press, of course. It’s a public hearing, thanks to the ‘open air’ provisions of the board charter.”

He wasn’t exactly rubbing his hands together in smug anticipation of the media’s likely reaction to his brilliantly timed little bombshell, but he might as well have been. Instead he straightened his already straight tie and ran his hand through his neatly trimmed gray hair as if readying himself for military inspection.

Sierra’s mother set the omelet and toast in front of her, as well as a small glass of orange juice. Sierra took a sip of the juice. She didn’t think she could handle something eggy and cheesy and spinachy right now.

When she was little, she used to have to leave the family room during any movie that had scary music in it. Even if it was a kids’ movie with a guaranteed happy ending, she couldn’t stand the suspenseful parts that happened on the way to the happy ending; she had to skip over all those tense, awful, nail-biting, knuckle-whitening bits. She’d hide out in the hall until it was safe to return and watch the closing scene of the faithful dog reunited with his little boy master.

“You haven’t even touched your breakfast,” her mother scolded.

Sierra took one nibble from one half of her piece of toast.

“Take just three bites of the omelet. Two bites.”

Sierra took one bite and tried not to gag on it, washing it down quickly with another swig of the orange juice, which tasted suddenly bitter, so acidic that she could feel it burning a hole in the lining of her stomach as scary music pounded inside her head, music for the scary movie of her own scary life.

* * *

At the Board of Education building, her father led the way down the hall to the small auditorium where board meetings—and high-profile expulsion hearings—were held, without needing to consult any building floor plan or ask anyone for directions. He carried a slim, expensive leather briefcase. Sierra knew at least one thing that was in that briefcase: police reports concerning Thomas Alford Besser forwarded from the State of Massachusetts.

Sierra and her mother walked hand in hand.

Sierra was wearing the same red plaid skirt she had worn on the day it all happened, together with a navy-blue blazer she had found at the back of her closet. Her father had been right that it made the perfect costume for acting the part of Unjustly Accused Honor Student.

Yesterday afternoon, as soon as she got home, Sierra had told her mother about her visit to Ms. Lin.

She hadn’t told her father.

Her mother hadn’t said, Oh, Sierra, how could you? or Sierra, I’m disappointed in you, or Sierra, I hope you learned your lesson. She had just hugged her and made her hot tea so that Sierra could warm her frozen hands on the steaming mug and hold it against her chapped cheeks.

At the back of the auditorium stood three television cameramen with all their equipment. Sierra recognized the three reporters who had interviewed her over the past week.

“Good luck, Sierra!” the blond reporter called over to her as Sierra walked through the door with her parents.

Sierra gave a small, cautious wave in return.

Mr. Besser was already there, talking to two other men: the lawyer for the school district and the superintendent of schools?

She tugged at her blouse to make sure it was tucked into the waistband of her skirt. She smoothed her hair, held back from her face with a white headband that matched her blouse.

Should she smile or look serious? Serious was probably best. She didn’t want the superintendent of schools to glare at her and ask, And what are you smiling at, young lady?

That was the kind of thing Ms. Lin would have said.

Sierra sat between her parents in the front row on the right side of the little aisle leading from the front to the back of the room. Mr. Besser and the shorter, stouter man sat on the other side; the shorter, stouter man must be the school district lawyer. The thin man, Abe Lincoln–gaunt, sat down at the small table on the raised podium in the front of the room, so he had to be the superintendent, Mr. Van Ek.

“I suppose we might as well begin,” Mr. Van Ek said.

Sierra’s mother’s hand tightened around hers.

Mr. Van Ek made some opening remarks about due process of law, too boring for Sierra to listen to, even though they probably were extremely significant for her fate. She could feel her father’s focused attention on every word.

“Tom?” Mr. Van Ek said then.

Mr. Besser stood up and approached the table.

For the first time Sierra noticed that Mr. Besser and her father were both wearing almost identical dark gray suits and white shirts. The only difference was that her father wore a regular long tie, while Mr. Besser wore his trademark bow tie.

Mr. Besser began by saying things Sierra had heard before, oh, so many times before. How important the new zero-tolerance policy had been to Longwood Middle School. How every student who enrolled in the school knew exactly what the policy said. Every single student and every single parent had signed a statement consenting to the policy.

“Here’s the form signed by Sierra Shepard and by her parents, Gerald and Angie Shepard.”

So the school had actually kept those dumb forms everybody had to fill out and sign at the beginning of the school year.

“Do I believe that Sierra deliberately brought that knife to school? No. But does the presence of that knife in her possession on school grounds constitute a violation under our zero-tolerance policy? Yes. Is this an offense that calls for mandatory expulsion? It is. Do I deeply regret the necessity for this final step in this unfortunate case? Yes, I do.”

Sierra could feel her father’s whole body growing tense; she could feel him drawing himself upright, leaning forward with squared shoulders, clenched jaw.

She wanted to excuse herself, say she needed to go to the bathroom, flee to the hall.

But now Mr. Besser was speaking directly, not to Mr. Van Ek, but to her.

“Sierra.”

She looked at him.

“Sierra,” he said again. “What you did.”

Blood pounded in Sierra’s temples: Was he going to betray her publicly for her forgery, tell three television reporters what she had done to Ms. Lin?

“Yesterday. About the choir trip.”

Sierra took a ragged, gasping breath.

She realized that she hadn’t told her parents, not even her mother, about the speech she had made to save the Octave’s trip. It seemed to have happened many years ago.

Mr. Besser gave Sierra a shaky smile, matching the unexpected tenderness in his tone, as if his voice might start to wobble the way hers did sometimes.

“Right now,” Mr. Besser told Mr. Van Ek, “our a cappella choir, the Octave, is on its way to perform at the Colorado Music Educators convention, an enormous honor for our school. This is a trip that was on the verge of being canceled because of a student protest on behalf of Sierra, a trip that would not be taking place right now if Sierra hadn’t come in yesterday morning to encourage—to implore—the rest of the choir to go without her. I haven’t known many students who could be so selfless, who make rules, respect, responsibility, and reliability their own personal concern. Sierra, I thank you.”

Sierra’s father had apparently had all he could stand.

“I presume,” he said, rising to his feet to interrupt Mr. Besser, “that the point of this hearing isn’t to commend this fine student leader but to expel her. Do I have that correct?”

“Yes, but I also want to take this opportunity to thank Sierra publicly for what she did for this school, for all she has done for this school, now that she has to be leaving us.”

Sierra saw that her father had already taken his sheaf of papers from his briefcase.

“So you are going to continue to make the case for expelling this fine student leader, who has done so much for this school in so many ways, despite one tiny, innocent mistake that she sought to correct immediately upon its discovery.”

He spoke as if he needed to be completely certain on this one crucial point before he said what he was about to say next.

Mr. Besser nodded. “Regretfully, I am. In the circumstances, I have no choice.”

“Well, then.” Sierra’s father remained unsmiling, but she knew that within his heart was wild, fierce exultation. The moment he had been waiting for had arrived at last, the moment for squishing Mr. Besser like a contemptible, hypocritical, soon-to-be-obliterated insect.

“It just so happens that I have some information to share with our esteemed superintendent of schools, and with our vigilant ladies and gentlemen of the press, information that I consider to be somewhat, shall we say, relevant to this case, or at least might be perceived to be relevant by those with a highly attuned sense of irony.”

Sierra forced herself to look at Mr. Besser. His ruddy face was several shades paler than it had been five minutes ago, and the kindly, regretful smile he had been beaming toward Sierra remained frozen in place, like the smile one might see on a corpse.

Not that Sierra had ever seen a corpse, or ever wanted to see one.

But it felt as if she were looking at one right now.

40

“Daddy.”

She was next to him, tugging at his arm.

“Daddy. I’m—I don’t feel well. I think I’m going to be sick.”

Mr. Van Ek was on his feet. Sierra could tell from his quick motions that he didn’t like it if people threw up in his special room for expelling students.

“Take her outside for a few minutes,” he instructed Sierra’s father.

Sierra’s mother h

ad jumped up, too. “Here, lean on me,” her mother said. “Let’s get you out in the hall, or to the ladies’ room. I knew you needed to eat a proper breakfast.”

Outside the door of the hearing room, Sierra dropped down onto a bench.

“Put your head between your legs if you’re feeling dizzy or light-headed. Or do you need to throw up? We passed the ladies’ room on the way in, it’s not far from here.”

“I’m okay,” Sierra said as her mother, sitting beside her, smoothed her hair. “I just felt—I can’t—”

Her father, still standing, looked mildly annoyed.

“Talk about bad timing,” he grumbled. “Now he knows what’s coming. Did you see his face? Now we’ve lost the element of surprise. Not that he can figure out how to save himself during a five-minute recess. Because there isn’t any way that he can save himself. Okay, sweetie, are you ready to go back in? Angie, see if you can get her a paper cup of water, or a Coke from the vending machine.”

“I’m not going back in,” Sierra said.

“But, honey,” her mother said, keeping her encircling arm around Sierra’s shoulders. “I think you have to. It’s your hearing, our hearing. We all need to be there.”

“That’s not what I meant. It’s Mr. Besser. Telling what he did. Telling everyone. It’s too—awful.”

“Oh, give me a break,” her father said. “What he’s doing to you—that’s not awful? Being a pompous hypocrite is one thing. Being a pompous hypocrite who is destroying a little girl’s life is another thing. I’m the father of that little girl, and I’m not going to allow him to do it unpunished.”

“Daddy.”

He was looking at his watch. Maybe he was wondering how long it was going to take to destroy Mr. Besser, given this unfortunate interruption, and if he was going to have to call his secretary to reschedule his late-morning appointments. Sierra waited until he looked back at her to continue.

“Daddy, I’m not a little girl.”

Not anymore.

Standing Up to Mr. O.

Standing Up to Mr. O. Lucy Lopez

Lucy Lopez Dinah Forever

Dinah Forever Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star

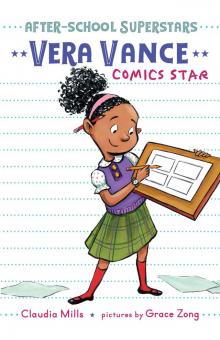

Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star Vera Vance: Comics Star

Vera Vance: Comics Star Izzy Barr, Running Star

Izzy Barr, Running Star You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman

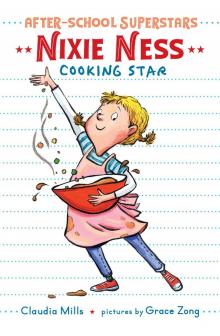

You're a Brave Man, Julius Zimmerman Nixie Ness

Nixie Ness The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish

The Totally Made-up Civil War Diary of Amanda MacLeish Basketball Disasters

Basketball Disasters Being Teddy Roosevelt

Being Teddy Roosevelt Losers, Inc.

Losers, Inc. The Trouble with Friends

The Trouble with Friends Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ

Simon Ellis, Spelling Bee Champ The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants

The Nora Notebooks, Book 1: The Trouble with Ants Annika Riz, Math Whiz

Annika Riz, Math Whiz Fourth-Grade Disasters

Fourth-Grade Disasters Pet Disasters

Pet Disasters The Trouble with Ants

The Trouble with Ants Write This Down

Write This Down Alex Ryan, Stop That!

Alex Ryan, Stop That! Kelsey Green, Reading Queen

Kelsey Green, Reading Queen How Oliver Olson Changed the World

How Oliver Olson Changed the World Lizzie At Last

Lizzie At Last Zero Tolerance

Zero Tolerance The Nora Notebooks, Book 2

The Nora Notebooks, Book 2 Cody Harmon, King of Pets

Cody Harmon, King of Pets Fractions = Trouble!

Fractions = Trouble! Makeovers by Marcia

Makeovers by Marcia One Square Inch

One Square Inch